This is the latest in our fortnightly series about the 16 triumphant teams in the European Championship before the 17th edition is played in Germany this summer.

We’ve looked at the Soviet Union in 1960, Spain in 1964, Italy in 1968, West Germany in 1972, Czechoslovakia in 1976, West Germany again in 1980, France in 1984, the Netherlands in 1988, Denmark in 1992, Germany in 1996, France in 2000 and Greece in 2004. Now it’s time for Spain’s second triumph, in 2008.

Introduction

What is understandably considered part of a glorious Spain hat-trick also feels like a triumph that is somewhat separated from the other two.

Spain won this tournament under the management of Luis Aragones rather than Vicente del Bosque. They did so with Marcos Senna in the holding role when his future replacement, Sergio Busquets, was still playing in the Spanish fourth tier.

Squad players included Juanito, Fernando Navarro, Sergio Garcia, Dani Guiza and Ruben de la Red, hardly names that spring to mind from a golden generation. But, in many ways, this Spain side was more exciting than the 2010 or 2012 iterations.

The manager

Luis Aragones turned 70 shortly after this tournament and was coming towards the end of a long career in management that included no fewer than six spells at Atletico Madrid, the club where he spent a decade as an attacker and won the Pichichi trophy as La Liga’s top goalscorer for the 1969-70 season.

He won the title with Atleti as a manager in 1977 and also took Barcelona to the Copa del Rey in 1988, but wasn’t considered a particularly progressive choice when appointed Spain manager in 2004. That year, he was filmed in a training session making racially offensive comments about Thierry Henry when speaking to Jose Antonio Reyes, his Arsenal team-mate.

(Denis Doyle/Getty Images)

In a footballing sense, Aragones’ major decision was to move on from Raul, the Real Madrid forward who had been excellent for the national side for a decade. Aragones believed Raul dominated the side too much, and took the remarkable decision to drop him definitively from the squad after World Cup 2006, despite the fact Raul was at that point Real Madrid’s all-time top goalscorer, Spain’s all-time top goalscorer and had just turned 29. That a Real legend was being overlooked by an Atleti legend did not go down well in some quarters.

You might be surprised to learn…

Despite being the man who helped bring about a revolution in passing football, Aragones had spent much of his career considered an old-school, back-to-basic, route-one merchant, essentially a Spanish Sam Allardyce or an earlier version of Diego Simeone — Atletico have often chosen the opposite footballing approach to the ‘galacticos’ down the road.

Most famously, there was a 1998 rant about Spain’s shift away from their physical, aggressive style. “We have dedicated ourselves to this idea that we all need to be brilliant on the ball, but no, Spain is not that kind of a football team… we should not try to go against our DNA,” he said.

But ultimately Aragones was a pragmatist, and pragmatists adapt to the tools at their disposal. Aragones, despite spending his career preferring more functional football, realised that with Xavi, Andres Iniesta and David Silva, playing more adventurous, front-foot football made sense. And in David Villa and Fernando Torres, Spain had strikers who wanted to be provided with through balls, not crosses or long balls.

Iniesta, left, helped make Spain tick (Clive Rose/Getty Images)

More than anything, he couldn’t rely on the physicality he often based his sides around, so had to adapt. Therefore, Aragones completed one of the most surprising U-turns in the history of football coaching.

Tactics

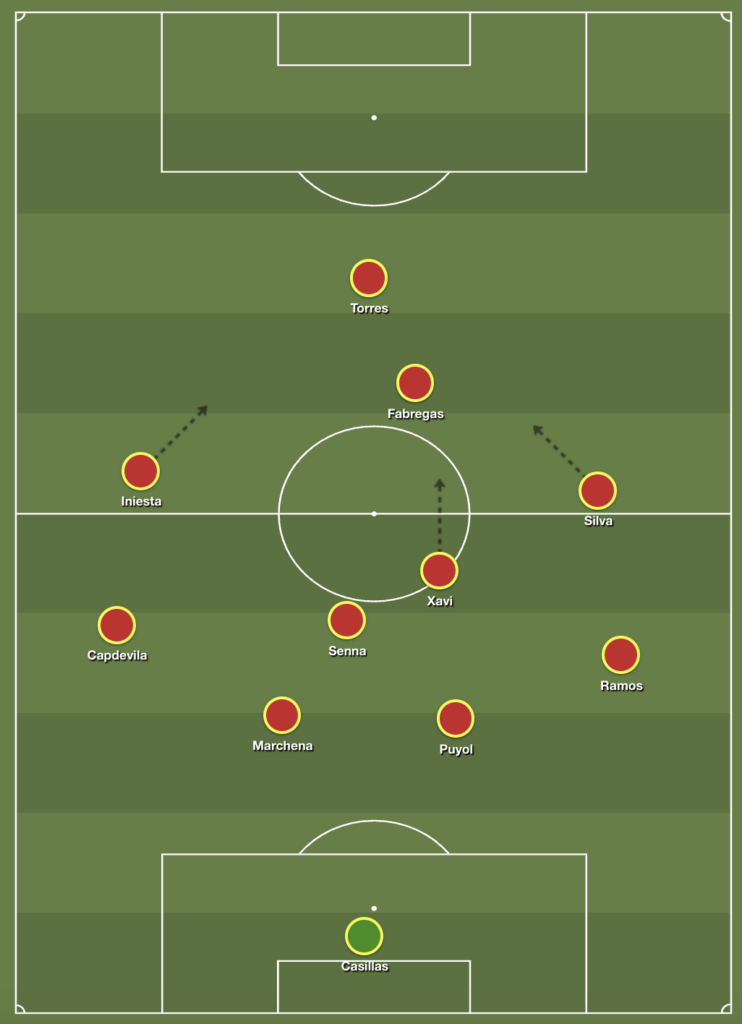

It was all based around possession and passing play but there was a freedom and a fluidity about this Spain side compared to the Del Bosque era, when Spain retained lots of players behind the ball and often only attacked with three players. Here, Xavi pushed forward into dangerous positions from deep in midfield, Iniesta and Silva played from the flanks but drifted around, interchanging and popping up on each others’ flanks. At times, it was slightly difficult to work out Spain’s precise system and 16 years on, it feels very different from the type of structured possession football we’ve come to expect.

(Shaun Botterill/Getty Images)

In terms of formation, it’s arguable that Spain struggled to find the right balance. This was because Aragones felt compelled to play Torres and Villa up front together. They had a good relationship, having played together in Spain’s youth systems. When Villa scored a hat-trick in the opening 4-1 victory over Russia, he made a point of celebrating his goals together with Torres. But the margin of victory slightly flattered Spain, and they weren’t much better in a last-gasp 2-1 win over Sweden, although both strikers scored.

Then came a 2-1 win over Greece with a completely rotated side in a dead rubber, a dreadful 0-0 quarter-final draw with Italy which was won on penalties. And then, 34 minutes into a tight semi-final with Russia, Villa limped off injured. The top goalscorer in the competition wouldn’t reappear — and suddenly Spain played their best football. Villa was replaced by Cesc Fabregas, who assisted two goals in an eventual 3-0 win over Russia.

“I don’t know whether Villa will play in the final,” Aragones said afterwards. “But in any case, tonight we played better with one forward than two.” And in terms of minutes per goal, Spain were twice as prolific at this tournament with one striker, compared to two — that system is depicted below.

Key player

Villa was the competition’s top scorer but, for the reasons above, can’t be considered the key player. Torres scored the winner in the final but felt like he was playing second fiddle to Villa beforehand. Xavi was probably the best player, winning the Player of the Tournament award, while Iniesta and Silva were also very good.

But the key player, in terms of his role in the side, was surely Senna. A Brazilian who spent his entire La Liga career with Villarreal, he was granted Spanish citizenship in early 2006 after only three years in the country. He was part of the squad at that year’s World Cup but became an integral part of the side in 2008.

Senna’s job was, essentially, to protect the defence and let others play — the Makelele role, really. “He gives us the balance we need and does the dirty work,” said Silva.

He was an occasionally physical player who was capable of making opponents tightly. The previously excellent Andrey Arshavin was nullified effectively in Spain’s 3-0 semi-final win over Russia, while Michael Ballack ended up bloodied after a clash in the final. But he was also an excellent passer. His technical quality was shown by the fact he was a regular set-piece taker for Villarreal, although more glamorous names tended to perform this role for Spain.

Senna protected Spain’s defence (Jamie McDonald/Getty Images)

Injuries meant he missed out on World Cup 2010 and he never regained his place in the squad. Senna, therefore, feels like the ‘most Euro 2008’ player of this Spain generation.

The final

Finals are rarely spectacular, or the best demonstration of a side’s technical ability. But there’s no doubt Spain were the better side here, taking the game to a Germany side who were yet to benefit from the rise of the Mesut Ozil, Toni Kroos, Mats Hummels and Manuel Neuer generation.

The most impressive thing about Spain, though, which does underline their approach at this tournament, is that having gone 1-0 ahead they continued to attack.

With 25 minutes remaining, Aragones brought on Xabi Alonso for Fabregas, which seemed like a bid to shut down the game. But Alonso popped up in the box for a good chance to make it 2-0 late on. Santi Cazorla on for Silva was pretty much a straight swap, as was Guiza on for Torres with 10 minutes remaining. In later years, Spain would use their possession play for defensive purposes — and they did keep three straight clean sheets in the knockout phase here — but this was a genuinely attack-minded side.

The decisive moment

In a way, a nice distillation of Spain’s style. Senna had the ball under little pressure in midfield, threaded it to a position between the lines for Xavi — in theory, his midfield partner, but playing a fluid role — and his ball in behind invited Torres to do what he did best, attacking into the channels.

Then there was clearly a mix-up between the useful unflappable Philipp Lahm and Jens Lehmann, with Torres using his speed and strength to nip in on the outside of Lahm before dinking the ball past Lehmann and just inside the far post.

Fernando Torres celebrates his goal in the final (Alex Livesey/Getty Images)

It is, a little unusually, a goal that seems to be shown primarily from the behind-the-goal camera angle, which makes Lehmann’s dive look a little timid, as if he’s diving out of the way of the ball — but Torres’ finish was perfect.

Were they clearly the best team?

Yes. There were some sparkling performances at the tournament from the Netherlands, who demolished France and Italy before falling to Russia, who briefly looked like they might shock Europe. Spain were not perfect — the system was never entirely set in stone, and the quarter-final against a weakened Italy was a truly dreadful game.

But after a defensive-minded Greece won Euro 2004, a typically tactical Italy won World Cup 2006, and at a time where the Champions League knockout stages was far more cagey than the type of action-packed tie we witnessed this week, this was a refreshing triumph for a modest, technically excellent group of players.

“Germany are not an ugly side, but it will be good for football if we win,” said Senna before the final. “It could open the minds of some coaches who think that only defensively you can win. It would show that you can attack and win.”

(Top photo: Getty Images)