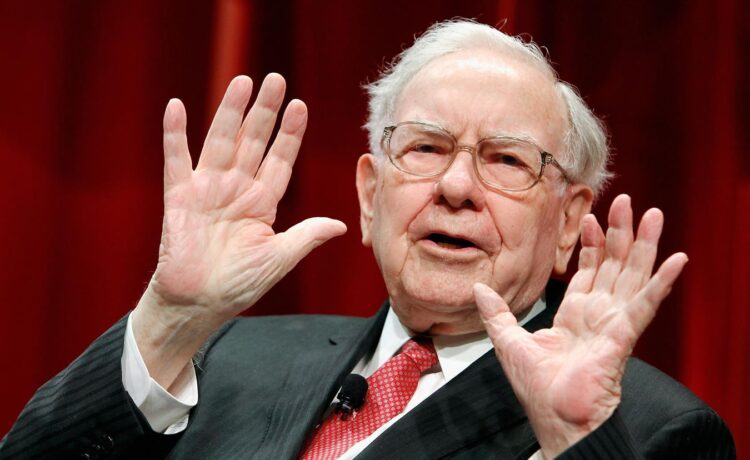

Warren Buffett has an extraordinary investment track record, but would he get fired by the … [+]

Mistakes fade away; winners can forever blossom. — Warren Buffett

Warren Buffett, Berkshire Hathaway’s CEO and Chairman, writes an annual letter to provide shareholders with an owner’s manual for the company and never fails to contain tremendous insights. Buffett has a unique gift for explaining complex investing topics in a digestible format. More about the long-term track record later, but Berkshire produced arguably the most remarkable extended performance for investors ever recorded. Even over a shorter period, Berkshire has significantly outperformed the S&P 500. As a rough proxy for the growth of the company’s intrinsic value, the book value growth has also far outstripped the appreciation of the S&P 500.

Berkshire Hathaway Performance

While Buffett’s letter offers countless lessons, this article will distill his annual missive into three timeless insights.

Lesson 1: Owning a business is superior to cash.

Berkshire shareholders can rest assured that we will forever deploy a substantial majority of their money in equities – mostly American equities although many of these will have international operations of significance. Berkshire will never prefer ownership of cash-equivalent assets over the ownership of good businesses, whether controlled or only partially owned. – Warren Buffett

While much ink has been spilled about Berkshire Hathaway’s $334 billion cash hoard, Buffett noted that considering the substantial size of its wholly owned subsidiaries, most of Berkshire’s investments remain in equities. To quote Buffett directly, “Despite what some commentators currently view as an extraordinary cash position at Berkshire, the great majority of your money remains in equities. That preference won’t change. While our ownership in marketable equities moved downward last year from $354 billion to $272 billion, the value of our non-quoted controlled equities increased somewhat and remains far greater than the value of the marketable portfolio.”

While his comments are accurate, the cash levels relative to Berkshire’s asset size are at an all-time high as far back as Bloomberg data exists. Using Berkshire’s market capitalization and some other minor adjustments as a proxy to capture the value of its wholly owned companies, cash levels are high but below mid-2005.

Berkshire Hathaway: Cash Level

Buffett makes the case that holding cash or bonds is not a good protection against inflation, as “Paper money can see its value evaporate if fiscal folly prevails. In some countries, this reckless practice has become habitual, and, in our country’s short history, the U.S. has come close to the edge. Fixed-coupon bonds provide no protection against runaway currency.”

Instead, he notes that good businesses with pricing power can adapt to inflation by saying, “Businesses, as well as individuals with desired talents, however, will usually find a way to cope with monetary instability as long as their goods or services are desired by the country’s citizenry.”

Long-term historical data returns across asset classes from 1928 to 2023 show that business ownership via stocks provided the highest annualized returns on both a nominal and real basis. These real, after-inflation returns are essential to maintaining and growing purchasing power. Buffett’s preference for owning good companies rather than cash becomes clear when one compares stock returns to cash equivalent assets, which has provided a more consistent but lower nominal return but has had a barely positive after-inflation return. Once taxes and expenses are considered, cash holdings, though more stable, have eroded purchasing power over time.

Long-Term Annualized Returns: 1928-2023

He also explained the secret of owning stocks when he said, “Understandably, really outstanding businesses are very seldom offered in their entirety, but small fractions of these gems can be purchased Monday through Friday on Wall Street and, very occasionally, they sell at bargain prices.”

It seems Buffett’s relatively large cash holding can be attributed to a lack of “compelling” opportunities. Buffett notes, “We are impartial in our choice of equity vehicles, investing in either variety based upon where we can best deploy your (and my family’s) savings. Often, nothing looks compelling; very infrequently, we find ourselves knee-deep in opportunities.”

Some of Benjamin Graham’s investment philosophies, as outlined in “The Intelligent Investor” book, remain the bedrock of Buffett’s investment process. Graham thought investors should look at stock holdings as owning a part of various businesses, like being a “silent partner” in a private company. Hence, stocks should be valued as a portion of the company’s intrinsic value, not as something with a constantly changing price on the stock market. An investor should take advantage of the stock market’s erratic view of a company rather than allowing it to dictate what one should do. Valuing stocks as a business and purchasing stock with a “margin of safety” enable investors to ignore the market’s manic or depressive states. For Graham, the “margin of safety” meant buying at a price below the “indicated or appraised value,” which should allow an investment to provide a reasonable return even if there are errors in the analysis.

Lesson 2: Capital allocation and the alignment of incentives create value.

Sixty years ago, present management took control of Berkshire. That move was a mistake – my mistake – and one that plagued us for two decades. Charlie, I should emphasize, spotted my obvious error immediately: Though the price I paid for Berkshire looked cheap, its business – a large northern textile operation – was headed for extinction. – Warren Buffett

Berkshire Hathaway would not be a household name without a momentous capital allocation decision early in Buffett’s leadership. In the mid-1960s, Buffett acquired control of Berkshire Hathaway, a New England textile company making suit linings. Instead of reinvesting in the sub-par textile business, he took the cash generated by it to invest in better businesses, including GEICO. The textile business was shuttered in 1985. Buffett gives Charlie Munger credit for convincing him to allocate to “wonderful businesses” rather than invest or reinvest in challenged businesses even though they are cheap. As Buffett says now, “Time is the friend of a wonderful business, the enemy of the mediocre.”

Buffett reiterated the importance of capital allocation decisions in this year’s letter: “Sometimes, I’ve made mistakes in assessing the future economics of a business I’ve purchased for Berkshire – each a case of capital allocation gone wrong. That happens with both judgments about marketable equities – we view these as partial ownership of businesses – and the 100% acquisitions of companies.”

He spent considerable space in the letter discussing Berkshire’s insurance business, which has some unique characteristics compared to typical companies. Part of the discussion involved capital allocation to the insurance business: “We must never write inadequately-priced policies in order to stay in the game. That policy is corporate suicide.”

Warren Buffett and, in the past, Charlie Munger have often spoken about the powerful force of incentives and being mindful of them when making decisions and compensation agreements. Buffett spoke to Berkshire’s alignment of incentives between the management and shareholders: “Moreover, Greg (Abel), our directors and I all have a very large investment in Berkshire in relation to any compensation we receive. We do not use options or other one-sided forms of compensation; if you lose money, so do we. This approach encourages caution but does not ensure foresight.”

He told the story of negotiating to buy Forest River, a recreational vehicle (RV) manufacturer, from the late Pete Liegl. Liegl continued to manage Forest River after selling to Berkshire until he passed away last year. Liegl negotiated an annual salary of $100,000, equal to Buffett’s salary, and an annual bonus of 10% of any earnings beyond what the company was earning at the time of the sale. Buffett added this to the compensation agreement: “OK Pete, but if Forest River makes any significant acquisitions we will make an appropriate adjustment for the additional capital thus employed.” This added adjustment wasn’t because he didn’t trust Liegl or Buffett wouldn’t have done business with him, but rather to align the incentives of profit growth with the cost of capital expenditures.

Lesson 3: Warren Buffett would get fired by most investors.

The world is overwhelmingly short-term focused. I mean, that is a world made to order for anybody that’s trying to think about what you do that should work over 5, or 10, or 20 years. – Warren Buffett at the 2023 annual meeting

Since Buffett began operating Berkshire in 1965, the stock has risen at an annualized pace of 19.9%. By contrast, the S&P 500 has had an annualized return of 10.4% during the same timeframe.

Annualized Total Returns (1965-2024)

Using annualized percentages doesn’t do Berkshire Hathaway’s outperformance justice. An investment of $10,000 in Berkshire Hathaway at the beginning of Buffett’s tenure would now be worth over $550 million. An investment in the S&P 500 would be worth over $3.9 million, which is overstated since it includes the reinvestment of dividends but no adjustment for expenses and taxes.

Berkshire Hathaway: Value Of $10,000

Despite its fantastic track record of performance, Buffett admitted some mistakes among his company purchases, “We own nothing that is a major drag, but we have a number that I should not have purchased.” Even with the enviable long-term performance, the combination of fallible decision-making and occasionally being out of sync with the markets has caused Berkshire Hathway to underperform the S&P 500 more often than most would expect.

For example, the return on Berkshire has trailed the S&P 500 for a full one-third of the calendar years. Looking at rolling three-year calendar years, Berkshire has underperformed a surprising 28% of the time, considering the exceptional long-term outperformance.

Berkshire Hathaway: Percentage Of Underperforming Periods Versus S&P 500 (1965-2024)

The chart of this rolling three-calendar-year performance underscores how easy it would have been for some investors to think Warren Buffett had sometimes lost his touch, sold the stock, and missed out on Berkshire Hathaway’s historic and breathtaking long-term performance.

Berkshire Hathaway: 3 Year Rolling Annualized Performance (1965-2024)

Many institutional and private investors still use the 3-year relative performance of their investment managers to make hire and fire decisions, even though it has been proven not to work for deciding whether to fire Warren Buffett by selling Berkshire Hathway or choose another investment manager.

Final Thoughts

Despite being a net seller of publicly traded stocks over the last nine quarters in a row, Berkshire did make a new purchase, Constellation Brands (STZ), according to the 13F filing with the SEC, released on February 14. The filing provides more details of the publicly traded stock portfolio changes. The insurance business was the primary driver of robust positive operating earnings growth in 2024, but even operating income growth excluding insurance hit double-digits. This was all despite 53% of Berkshire’s 189 operating companies seeing earnings declines in 2024.

While the letters have generally become shorter recently, Warren Buffett never disappoints with his annual letter as Buffett is a master teacher and investment genius. He reinforces the timeless lessons with new illustrations and occasionally unveils something new in his bag of tricks. While none of the concepts discussed are new, Buffett reinforced insights relevant to the current state of investing, particularly Berkshire Hathaway’s insurance business. The next major update will be in early May, when many of us will make our annual pilgrimage to Omaha to attend the annual meeting, otherwise known as the Woodstock for Capitalists.