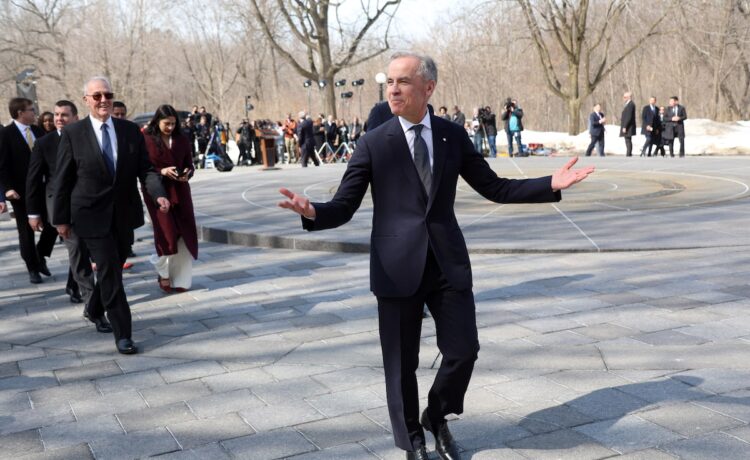

Mark Carney was sworn in as Canada’s prime minister on March 14, taking charge of a country rattled by a breakdown in U.S. relations since President Donald Trump’s return to power.DAVE CHAN/AFP/Getty Images

Mark Carney wants to move fast and build things.

There was nothing subtle about the new Prime Minister’s desire to differentiate himself from his predecessor Justin Trudeau, to prove himself more businesslike and results-oriented, after he was sworn into the job on Friday.

It was on display in his first public remarks, which eschewed compelling prose in favour of brisk promises to run an “action-oriented” government that gets straight to work on a shorter list of priorities.

It was evident as well in the size of his new cabinet, down from 37 to 24 members, with limited effort to achieve regional balance or to manage the egos of several former ministers who were left out – including one of his erstwhile leadership rivals, Karina Gould.

But perhaps the most telling of Mr. Carney’s attempts to speed up the way things work in Ottawa – and potentially the most consequential, if he gets a chance to actually govern after the election he is about to call – is his choice of Finance Minister.

François-Philippe Champagne is not necessarily the person to put in that job for deep soul-searching about the future of the Canadian economy, amid a trade war with the United States and a crumbling international order. That’s more up the alley of Chrystia Freeland, the deeply inquisitive former journalist who filled that role for nearly five years, and has now been tasked with Transportation and Internal Trade.

The reality, though, is that Mr. Carney will probably do much of the big-picture economic and financial direction-setting himself. There will only be so much elbow room for any finance minister, serving under someone who was one of the world’s best-known bank governors.

What Mr. Champagne instead brings to the table is an unusually energetic and transactional management style that, unlike many of the colleagues who served alongside him in Mr. Trudeau’s cabinet, is less about plan-making than about follow-through.

The former corporate lawyer’s trajectory, since he first entered cabinet in 2017, hasn’t been totally smooth; he struggled during a stint as foreign minister, though that wasn’t unusual under Mr. Trudeau. But he really found his groove over the past four years as minister of innovation, science and industry, highlighted by his pursuit of a Canadian electric-vehicle supply chain.

That prospect seemed abstract and remote when he took the job, and the standard course of action in Ottawa would have been to spend years developing a road map for achieving it. Mr. Champagne pretty much skipped that step, took it as his marching orders to start landing anchor projects, ignored skeptics within and outside his own government and set about one of the most aggressive courtships of international investment this country has seen – eventually being able to boast several massive battery factories, as well as a first wave of battery-material suppliers.

That sort of dog-with-a-bone mentality is presumably what Mr. Carney is hoping he will bring to Finance, albeit with a very different set of imperatives. Rather than being a salesperson to the rest of the world, he will need to direct his energy within government, and particularly within his own department.

Nimbleness is not a word generally associated with the Finance Ministry. That’s partly due to warranted prudence from bureaucrats trying to reality-check politicians’ ambitions. But there have also been frequent complaints around Ottawa of them throwing up roadblocks to unfamiliar policies, with the slow rollout of energy and clean-technology investment tax credits – a form of business incentive with which Canada has limited history – one oft-cited example.

So the question now is whether, if the Liberals hold onto government, Mr. Champagne can instill more of a mission in that department – and in service of what, exactly.

Mr. Carney has already put a forward a few ideas that could challenge Finance orthodoxy. His proposal to restructure budgets to separate operational spending from capital spending, to prioritize the latter in the name of long-term nation-building projects, is one such example.

But many of the finance-related components of his leadership-campaign platform – including promises to cut taxes, trim operational spending, use more public dollars to attract private investment, support trade diversification and replace consumer-facing carbon pricing by upping the focus on industrial emitters – were too broad to be actionable by Mr. Champagne or anyone else.

It will be Mr. Carney’s job, over the course of the general-election campaign and in its immediate aftermath, to give more clarity on what he wants done so quickly.

The same will cut across other departments, too. It might help that fewer ministers will be tripping over each other, and that cabinet meetings will be less unwieldy. Still, more details will be needed from Mr. Carney on how much and in what form he wants to increase defence spending; what sorts of energy projects he’s most eager to fast-track; how he intends to strike the right immigration balance between attracting skilled workers and not overheating the system.

But no cabinet appointment is more telling of what sort of government a prime minister wants to run than Finance.

Mr. Carney, despite his dry technocratic manner, clearly wants Canadians to know he won’t be too patient in responding to the threat posed by Mr. Trump. He’s chosen someone who only moves in a high gear to prove it.