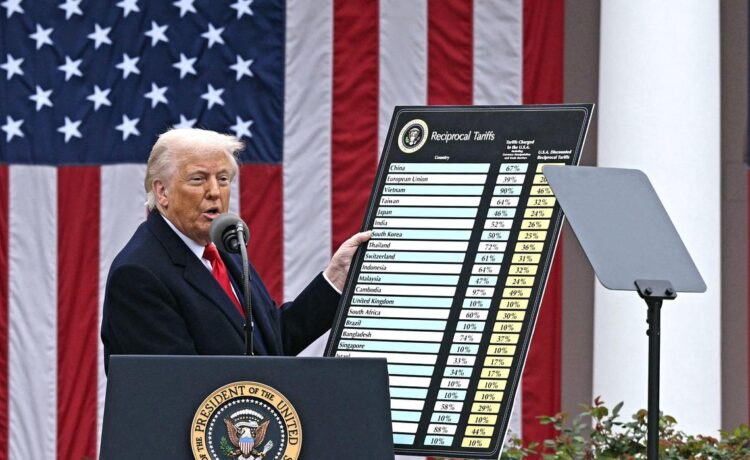

WASHINGTON – Framing it as a declaration of economic independence, US President Donald Trump announced sweeping tariffs on April 2 in an attempt to replace free trade with “fair” trade.

In his most ambitious economic policy, which he said will make America wealthy again, he announced a tariff of 10 per cent on all goods coming into the US from anywhere in the world, including Singapore.

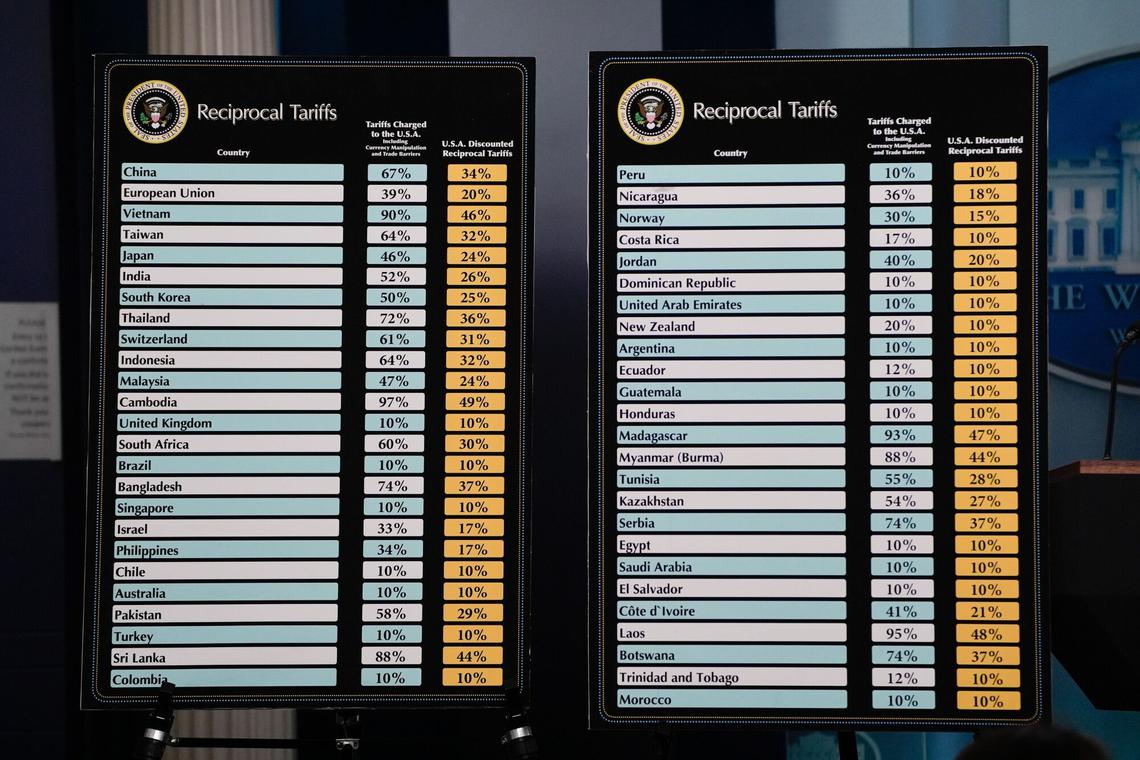

He also imposed hefty “reciprocal” tariffs on at least 60 trading partners, who he said slapped excessively high duties on American products.

The harshest burden fell on Asian economies, with the highest rate of 49 per cent imposed on Cambodia.

The tariffs on China stood at 34 per cent, on top of the 20 per cent that Mr Trump has already imposed on it for not doing enough to combat the trafficking of the deadly synthetic opioid, fentanyl.

The tariff on Vietnam was at 46 per cent, Thailand 36 per cent, Indonesia and Taiwan at 32 per cent each, Malaysia 24 per cent and the Philippines at 17 per cent.

Among the few Asian nations hit with under 30 per cent were allies Japan at 24 per cent and South Korea at 25 per cent. India, which Mr Trump named as imposing some of the steepest duties on US-made goods, faced a 26 per cent tariff.

Canada and Mexico are excluded from the reciprocal tariff regime, while the European Union faces a 20 per cent tariff and Australia 10 per cent.

Mr Trump also imposed hefty “reciprocal” tariffs on at least 60 trading partners, who he said slapped excessively high duties on American products. PHOTO: BLOOMBERG

Ms Wendy Cutler, vice-president of the Asia Society Policy Institute and former acting deputy US trade representative, said: “Hitting Singapore, a close ally and an FTA (free trade agreement) partner with an open economy, comes as a surprise.”

Under the US-Singapore Free Trade Agreement, in effect since 2004, Singapore applies zero tariffs on US products, as long as they qualify as originating goods under the FTA’s rules of origin.

The exception is for Singapore’s goods and services tax, which applies to both imported and domestic goods, at the rate of 9 per cent. Additionally, certain goods such as alcohol and tobacco face excise taxes.

Ms Cutler said Asia seemed to have been at the receiving end.

“Even US FTA partners in the region were recipients of new tariffs, with South Korea’s rate at 25 per cent unusually high given that over 99 per cent of US exports to Korea enter duty-free,” she said, in a reference to the US-Korea Free Trade Agreement that took effect in 2012.

“Our trading partners will not view these rates as ‘kind’ or justified, and many will be under domestic pressure to respond with their own measures,” she added.

Mr Trump argues the reciprocal tariffs will narrow what he says is an “unfair” gap between the duties the US levies on imported goods and what other countries charge on American products.

His policy marks the most extensive reworking of the international order since World War II, which the US helped to put in place. It is likely a matter of time before America’s trading partners retaliate with their own tariffs, a pattern that raises the possibility of a devastating global trade war.

“April 2, 2025, will forever be remembered as the day American industry was reborn, the day America’s destiny was reclaimed and the day that we began to make America wealthy again,” Mr Trump declared, as he announced the tariffs at an event attended by his Cabinet, prominent members of Congress and his Make America Great Again supporters.

“Foreign nations will finally be asked to pay for the privilege of access to our market, the biggest market in the world,” he added.

“Because we are being very kind… we will charge them approximately half of what they have been charging us, so the tariffs will not be fully reciprocal.”

The universal tariffs will take effect at midnight on April 5 (12pm on April 6, Singapore time), while the reciprocal tariffs will kick in at midnight on April 9.

Ahead of the announcement, Mr Trump’s officials said that reciprocal rates were derived from numerous factors, such as the country’s tariff rates, value-added taxes, non-tariff measures like subsidies and foreign exchange policies.

The latest batch of tariffs comes on top of 25 per cent tariffs on imports of steel and aluminium, which took effect on March 12, and the same rate on foreign cars, which kicks in this week.

In assessing the impact of the tariffs, analysts have drawn parallels with the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act of 1930, which imposed 20 per cent tariffs on most imports and contributed to the Great Depression.

Mr Trump has long argued that a lack of reciprocity is what led to a “large and persistent annual trade deficit that’s gutted out industries and hollowed out key workforces”.

Economists challenge some of those assumptions and point out that the impact includes inflation and may trigger a recession.

Mr Trump has also described the tariffs as incentives for foreign companies to relocate their factories and make their goods in the US. Several large companies have announced plans for new investments running into hundreds of billions of dollars.

But the tariffs will not really stoke US manufacturing, said Dr Marcus Noland, a senior fellow and executive vice-president at the Peterson Institute for International Economics in Washington.

“The modelling work that I’ve done, examining various tariff proposals, does not show that revitalisation of manufacturing occurring,” he said.

“To the contrary, it shows that these proposals are likely to reduce the role of manufacturing in the economy by making the US a high-cost location for production,” he added.

“If it boosts anything, it’ll boost economic activities that are not tradable across international borders, things like real estate, hotels, retail and restaurants.”

Resources will migrate into the service sector because the dollar will appreciate, which will make it harder for the US to compete in internationally traded goods, he said.

Economists say tariffs can cause the US dollar to strengthen by raising the cost of imports, reducing demand for foreign goods, and thus lowering the need to sell dollars for foreign currency. The decreased supply of US dollars can increase the currency’s value.

Dr Philip Luck, former deputy chief economist at the State Department during the Biden administration, said even if the manufacturing returns, jobs may not.

“The US is still the second-largest manufacturing economy in the world. But the problem is, manufacturing is done by machines and automation. So we can bring back a lot of manufacturing, but you’re not going to bring back a lot of jobs,” he said.

Join ST’s Telegram channel and get the latest breaking news delivered to you.