Opinion editor’s note: Star Tribune Opinion publishes a mix of national and local commentaries online and in print each day. To contribute, click here.

•••

Two recent opinion pieces have warned about a proposed change under the 1980 Bayh-Dole Act to enlarge the “march in” rights of the federal government. One was a hyperpartisan editorial from the Wall Street Journal (“Biden’s patent plan threatens innovation,” Dec. 18). The other, a commentary, was a more measured analysis by a former business school dean and director of the Federal Trade Commission (“New treatment for drug prices risks side effects,” Opinion Exchange, Jan. 3).

The Bayh-Dole Act is federal legislation that enables a university to obtain a patent for an invention even though public funds are used for the research. The university then sells a license to a company in the private sector to use the patent. The premise is that everyone will make (tons of) money from selling the drug or other product.

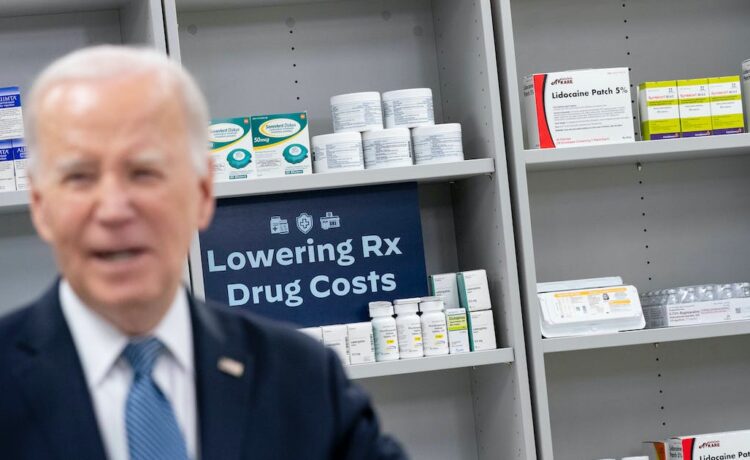

The proposed policy change would allow the federal government to intervene if a commercial company sets an unreasonable price or unreasonably limits the availability of the drug or other product to the public. This is all too much for the Wall Street Journal. It asserts that the “Biden administration cares more about expanding government control over the private sector than about accelerating lifesaving treatments” and that “stealing IP [intellectual property] is now part of Bidenomics.”

This description fails to take into account all the consequences of the 1980 law. The mere prospect of large revenue gains for universities produced huge increases in the operating expenses and capital costs related to research. Yet only a few universities realize sufficient revenue to generate a positive return on investment after deducting all the costs for personnel and for the construction and maintenance of buildings and equipment.

In fiscal year 2023, according to a Board of Regents report, the University of Minnesota received $1.13 billion in research grants from all sources and collected $16.6 million in licensing revenue. The total research expenditures were $1.2 billion. (See pages 12-20.)

The law of unintended consequences is also part of a more complete analysis. The dreams of university administrators for huge financial payoffs for their own institutions promotes secrecy that blocks the free flow of information among scholars. The quest for the advancement of knowledge now has a seductive competitor — the quest for riches.

As costs have mounted and federal grants for research have declined, the universities have looked more and more to corporate sponsors. This has produced a blurring of the priorities of nonprofit institutions of higher education and the priorities of for-profit corporate sponsors. Such a creeping conflict of interest surfaced at the U of M when a patient enrolled in a clinical study of a psychiatric drug died by suicide (“Legislative auditor says U should suspend psychiatric drug trials,” March 28, 2015).

The increasing reliance on corporate funds can also cause senior administrators to attempt to block the public presentation of research that might offend major corporate donors, such as agricultural companies at land grant universities. This occurred at the university with the aborted attempt to prevent a screening at the Bell Museum of a documentary film by a Peabody award-winning director. “Troubled Waters” shows the effect of large runoffs of fertilizers and pesticides into the Mississippi River (“Minneapolis documentary maker is a catalyst for change,” May 9, 2015).

The warnings about the potential loss of drugs from the proposed new federal policy should be tempered by an acknowledgment of both the adverse consequences of the existing law and the enormous profits of the pharmaceutical companies made possible by the investment of public funds.

Michael W. McNabb, of Lakeville, is an attorney.