(Bloomberg) — In hindsight, the telltale signs of trouble were piling up: the Zoom calls where the owner kept his camera off; the angry pushback from his brother when investors asked for invoices to back up their loans; the frequent late payments to suppliers; and the whispers of large off-the-books financing arrangements.

That so few outside of First Brands had a full view of all the red flags around the auto-parts supplier before it imploded spectacularly late last month, stands as a stark example of the growing risks of money flooding into the opaque world of private financing. How it operated, where it got its money and even the people running it were largely a mystery.

Most Read from Bloomberg

By the time it all came crashing down, the company’s sprawling network of auto-parts factories and distribution centers was on the hook for over $10 billion to some of the biggest firms on Wall Street: Jefferies, UBS and Millennium, among others.

While the full extent of the damage — and what exactly went wrong — remains unclear 11 days after First Brands declared bankruptcy, the stakes were raised on Wednesday night when one of First Brands’ financial partners made an emergency court filing calling for an independent investigation into $2.3 billion tied to the company it said had “simply vanished.” Federal prosecutors are now looking into the circumstances around the bankruptcy, though the inquiry is in the early stages, Bloomberg reported Thursday.

In the meantime, the repercussions are rippling through the financial industry and beyond.

Raistone, the company that called for the investigation, and that had facilitated First Brands’ short-term borrowing, derived 80% of its revenue from First Brands and has already cut roughly half of its employees. It is now part of the official committee representing unsecured creditors in court. The O’Connor hedge fund unit owned by UBS is facing such significant losses that Cantor Fitzgerald is now trying to renegotiate the terms of its acquisition of the business.

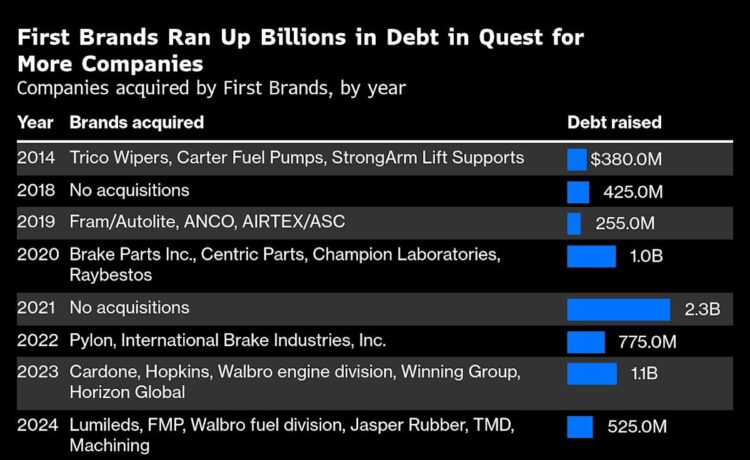

Jefferies is facing redemption requests from investors who had money in a hedge fund arm of the bank, Point Bonita Capital, which had a quarter of one of its portfolios — some $715 million — tied to First Brands. The situation is a particular threat to Jefferies’ reputation because the bank also helped First Brands sell a significant chunk of its long-term loans over the past decade.