Mental health apps have become increasingly common over the past few years, particularly due to the rise in telehealth during the coronavirus pandemic.

However, there’s a problem: Data privacy is being compromised in the process.

“Data is incredibly lucrative in the digital space,” Darrell West, senior fellow at the Brookings Institution, told Yahoo Finance. “That’s how companies are making their money. Many large companies derive a substantial part of their revenue from advertising. People want to target their ads on particular people and particular problems. So there’s the risk that if you have a mental health condition linked to depression, there are going to be companies that want to market a medication to people suffering in that way.”

In 2023 the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) ordered the mental health platform BetterHelp, which is owned by Teladoc (TDOC), to pay a $7.8 million fine to consumers for sharing their mental health data for advertising purposes with Facebook (META) and Snapchat (SNAP) after previously promising to keep the information private.

Cerebral, a telehealth startup, admitted last year to exposing sensitive patient information to companies like Google (GOOG, GOOGL), Meta, TikTok, and other third-party advertisers. This info included patient names, birth dates, insurance information, and the patient’s responses to mental health self-evaluations through the app.

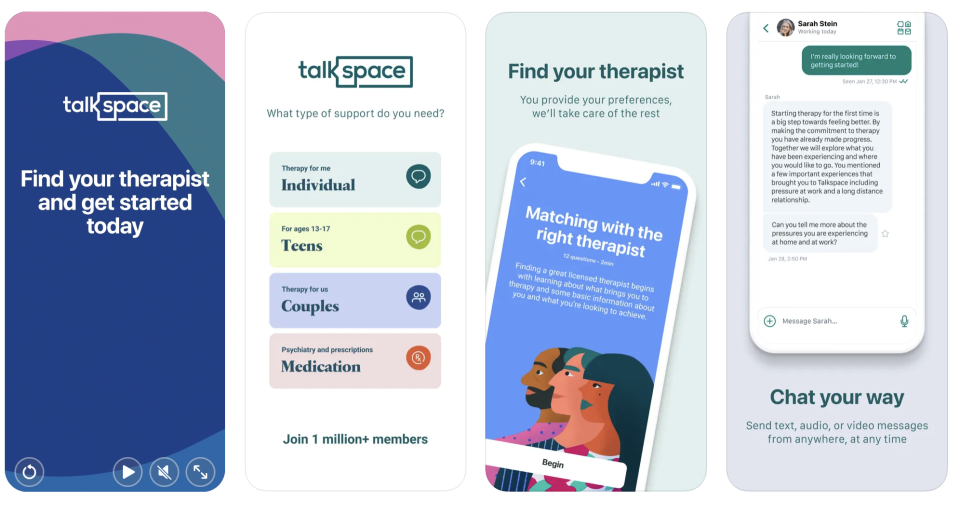

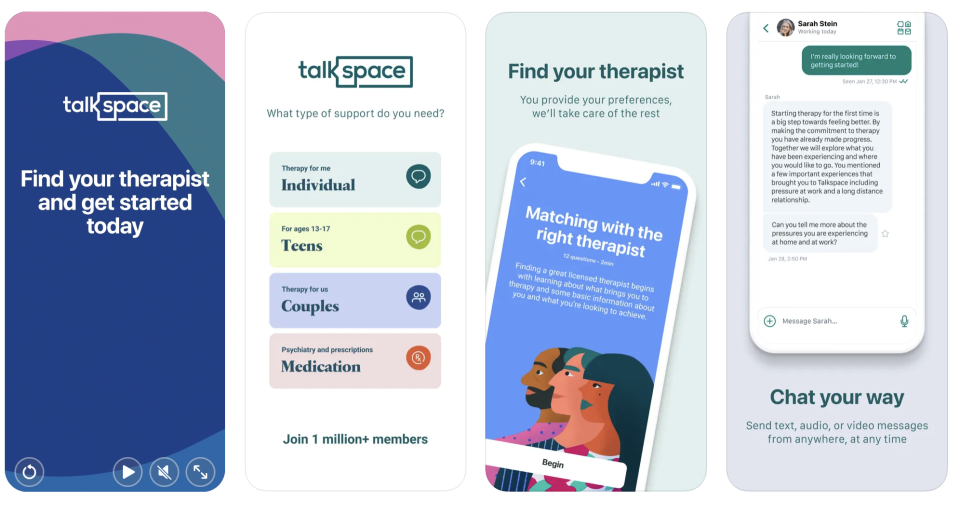

And mental health app Talkspace’s privacy policy explicitly states the company can “use inferences about you made when you take their sign-up questionnaire that asks questions about things like your gender identity, sexual orientation, and whether you’re feeling depressed (all before you’re ever offered a privacy policy) for marketing purposes, including tailored ads.”

Mental health app policies ‘seemed like a money grab’

Overall, according to the Mozilla Foundation’s Privacy Not Included online buyer’s guide, only two out of the 27 mental health apps available to users met Mozilla’s privacy and security standards in 2023: PTSD Coach, a free self-help app created by the US Department of Veteran Affairs, and Wysa, an app that offers both an AI chatbot and chat sessions with live therapists.

Mozilla began assessing these apps in 2022 due to their surge in popularity during the height of the coronavirus pandemic.

“We were concerned that maybe the companies might not be prioritizing privacy in a place where privacy seemed paramount,” Privacy Not Included program director Jen Caltrider told Yahoo Finance.

An overwhelming majority of the apps fell short of Mozilla’s privacy and security standards in both 2022 and 2023, due to how they control user data, track records, secure private information, or use artificial intelligence.

“It seemed like a money grab, capitalizing on vulnerable people during a bad situation, and it felt really icky,” Caltrider said.

Telehealth is a ballooning industry

A report from Grand View Research estimated that the global telehealth market was valued at roughly $101.2 billion in 2023 and is projected to grow 24.3% on an annual basis from 2024 to 2030.

North America represents the largest market share in the world at 46.3%, though other countries are quickly adopting telehealth as well.

Mental health apps are also projected to grow substantially between 2024-2030, with Grand View Research estimating a compound annual growth rate of 15.2% after the global mental health app market reached $6.2 billion in 2023.

This also means there are significantly more opportunities for personal data to be exposed. A December 2022 study of 578 mental health apps published in the Journal of the American Medical Association found that 44% shared data they collected with third parties.

“I sit on two sides of the fence,” Diane O’Connell, attorney and president at Sorting It Out Inc., told Yahoo Finance. “On one end, the convenience of [mental health apps] has really provided greater access to mental health and physical healthcare. But on the other end, having private health information hackable is a concern as well.”

Someone using one of these mental health apps to seek help for depression or anxiety may start to see advertisements for antidepressants, even if they have never expressed interest in taking medication.

Legal loopholes

Data brokers capitalizing on mental health data is nothing new. A February 2023 report from Duke University found that out of 37 different data brokers that researchers contacted about mental health data, 26 responded, and 11 firms “were ultimately willing and able to sell the requested mental health data.”

It’s also completely legal.

HIPAA — the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act — was implemented in 1996 by President Clinton as a way to “strike a balance that permits important uses of information, while protecting the privacy of people who seek care and healing.” It’s now considered America’s primary healthcare privacy law.

However, not all entities are bound by HIPAA, including many mental health apps. According to HIPAA Journal, the law applies to “the majority of workers, most health insurance providers, and employers who sponsor or co-sponsor employee health insurance plans.” Those who do not have to abide by HIPAA include life insurers, most schools and school districts, many state agencies, most law enforcement agencies, and many municipal offices.

“HIPAA only applies between a conversation or information shared between a doctor and their patient,” Caltrider said. “A lot of these [mental health] apps, you’re not considered patients in the same way. Some of them you are. I think Talkspace is a good example of [how] once you become a client of Talkspace, they have a different privacy policy that will cover your interactions than before you become a client. They have it so that when you’re a client, you have a relationship with an actual therapist as opposed to a coach.”

This happens often with talk therapy apps, Caltrider explained, adding that HIPAA “doesn’t cover the vast majority of what a lot of people are sharing with mental health apps.”

“People don’t understand that [HIPAA] only covers the communications between the healthcare provider, and so these apps aren’t covered by that,” Caltrider said. Even if HIPAA applies to the conversation between you and a therapist, some of the metadata collected about your appointment times and which apps you use for video calls may not be covered by the law.

HIPAA protections are also contingent on the type of provider you’re meeting with; a licensed therapist is considered a healthcare professional, but an emotional coach, professional coach, or volunteer is not.

The ‘Napster argument’

Another legal loophole that data brokers and mental health app providers are able to use is in the Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health (HITECH) Act of 2009, which extended HIPAA guidelines to those considered “business associates of covered entities,” the HIPAA Journal stated.

According to O’Connell, many private equity firms bought medical practices and hospital networks after Congress passed the Affordable Care Act. Because the investors conducting these M&A deals were not in the medical industry, O’Connell explained, the HITECH Act didn’t apply to them since they weren’t considered business associates — a billing, healthcare, or health insurance company — under HIPAA.

“It created this confusion of how do you exchange data in these merger and acquisition deals when you’re not allowed to exchange personal health information with the company who’s actually trying to buy you?” O’Connell said.

That’s where terms and conditions come into play. O’Connell called it the “Napster argument,” alluding to the former peer-to-peer file-sharing network that shut down permanently in 2001 following multiple lawsuits related to music copyright infringement.

“Napster wasn’t stealing music — it was just creating a platform for people to share it,” O’Connell said. “So you come up with these different arguments on how the regulations don’t apply, and then you create a fact pattern that fits your narrative until somebody takes you to court, and then the judges decide.”

According to West, the main issue is that the US lacks a national privacy law, meaning “there aren’t a lot of regulations that govern behavior in this area, and so there’s a wide range of companies out there. Some of them take privacy very seriously, and others do not.”

“We are not opposed to mental health apps,” West said. “There are many virtues. It brings medical services to a wider range of people because you don’t have to physically go to a doctor’s office.”

West added, “We just want to make sure that people are aware of the risk and that there are better protections built in. And people need to look at the privacy practices of the particular app they’re using to make sure it has the protections that the individual patient wants.”

—

Adriana Belmonte is a reporter and editor covering politics and healthcare policy for Yahoo Finance. You can follow her on Twitter @adrianambells and reach her at [email protected].