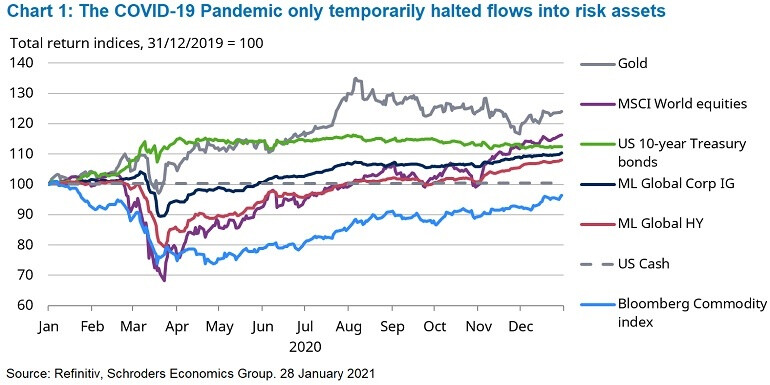

The Covid-19 pandemic was the dominant investment theme of last year and, for a short period in the spring, hit portfolios badly.

Past performance is not a guide to future performance and may not be repeated.

Markets in riskier assets such as shares and corporate bonds fell and were substantially down by Easter, but help came in the form of fiscal and monetary policy stimulus.

Interest rates were cut either to record lows, or to match past lows. Central banks also restarted aggressive quantitative easing. This involved buying up large amounts of bonds and other securities, with the goal of increasing liquidity and stability in the financial system, and encouraging lending.

Meanwhile, governments committed to running huge deficits, the likes of which have not been seen since the Second World War.

These measures helped to lift risk assets, with equities and corporate bond markets ending the year in positive territory. Holders of government bonds and gold also did well thanks to the additional liquidity provided by stimulus measures.

Past performance is not a guide to future performance and may not be repeated.

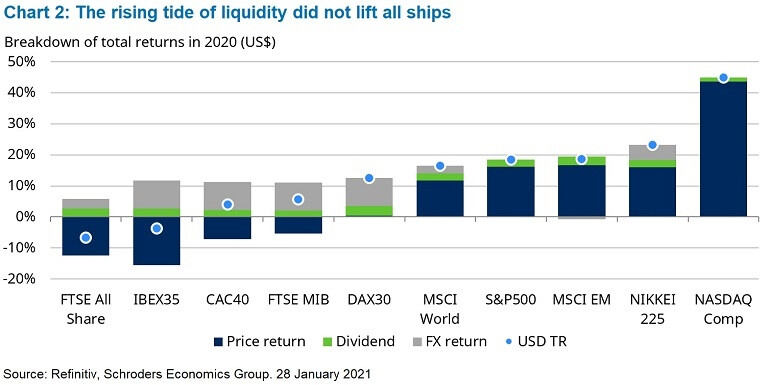

Though global equities ended 2020 with a positive total return, there were huge differences between the performance of individual regions and sectors.

Clearly, some sectors such as IT and communication service providers benefited from the pandemic related lockdowns, which helped lift the US’ tech-heavy Nasdaq index to record highs.

Commodities producers struggled due to a collapse in demand, while banks also lagged, as loose monetary policy lowered interest rates and hit the profitability of banks. These factors contributed to the underperformance of the UK FTSE All Share, and Spain’s IBEX35, though the former was also weighed down by Brexit uncertainty.

Pandemic related restrictions have lasted longer than expected, but they should be lifted in the coming months as case numbers fall, and newly approved vaccines are distributed. As a result, investors could see a stronger recovery in those markets that underperformed last year.

2020 was another odd year when both equities and government bonds generated positive returns. This has only happened on a few occasions, and typically when huge amounts of liquidity are injected into financial markets, as was the case in response to the Covid-19 pandemic.

However, benchmark 10-year government bond yields are either at or close to record lows. As bond prices rise as yields fall, such levels mean that further significant gains in prices will be difficult to achieve.

Here on the economics team at Schroders, our forecast has central bank interest rates in major markets on hold in 2021, and for most, in 2022 too. Quantitative easing is also expected to last through most of this year. This should relieve the pressure for bond yields to rise and protect holders to some degree.

We may see investors choose to reduce their bond holdings in the coming year, unless they are being held to “hedge” their exposure to riskier assets.

A hedge is a position held by an investor with the aim of offsetting risks held elsewhere in a portfolio.

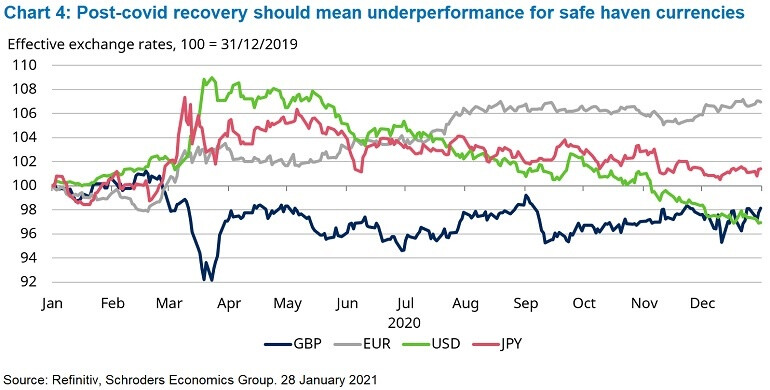

With government bond yields so low, investors have been using alternative hedges, such as the US dollar and the Japanese yen, to great effect.

We saw this in March 2020, when the value of these two currencies perceived as safe havens rose sharply, then subsequently declined slowly over the course of the year..

Our baseline forecast is for a strong economic recovery in most parts of the world, and so we also expect safe haven currencies to underperform. Nevertheless, in the event of another shock, the dollar and yen would be favourites once again.

Past performance is not a guide to future performance and may not be repeated.

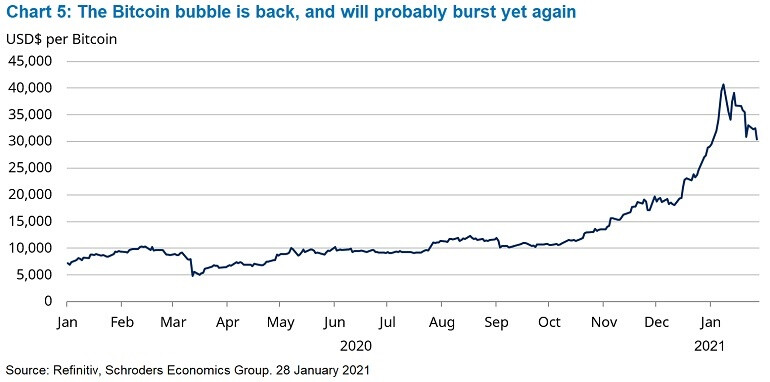

One of the big talking points in markets is the sudden resurgence of Bitcoin and the perception of it as a viable asset class.

Many proponents of Bitcoin point to the huge liquidity unleashed by central banks to aid the economy, and warn that it will eventually cause inflation. By design, the crypto currency has a limited supply, and so supporters promote it as a real asset that should flourish if inflation rises.

In reality, it is hard to pinpoint exactly why or when crypto currencies gain and lose popularity. Bitcoin sold off alongside most risk assets in March 2020 and initially did not react much to the announcements by central banks of increased quantitative easing.

The sudden surge only began in October, with the price rising 282% between 1 October and 8 January. Since its peak, it has lost over 25% of its value without an obvious reason, highlighting both its high risk and erratic performance.

Many investors, including some large institutions, are considering adding Bitcoin to their portfolios. It is worth asking why use a crypto currency that has no physical presence, over a real asset such as physical commodities, or property. The answer for too many will be its past performance based on speculation.