In recent months, there have been subtle but consistent signs of uneasiness among investors in the U.S. government’s debt securities. So far, these signs have not caused any drama in the debt market, but the latest ‘hint’ from the market suggests that investors may soon be putting on a show for us.

Put simply, there is a case to be made that investors have begun asking for a risk premium to invest in U.S. debt. The data is far from conclusive, but it is also not something that we can easily dismiss.

Before we get to the numbers, let me make clear that the risk premium issue should be handled with extra care. The premium is exactly what it sounds like: a mark-up on the interest rate that an investor demands in order to buy a security. It means that an investment in U.S. debt would no longer be risk-free.

It also means that if rumors began flying that a risk premium is needed for holding U.S. debt, it could cause destructive instability well beyond the debt market. At the same time, precisely because of the explosive implications of a risk premium, we need to examine whatever signs of it that the market exhibits.

If a risk premium does indeed become an established mark-up on U.S. debt, it would be very bad news for Congress and the president. The U.S. Treasury securities would on a broad scale lose their benchmark status as a reliably risk-free portfolio anchor. There would also be major consequences for Congress, which would lose control over the cost of its own debt.

There would be no reason to discuss a risk premium if it wasn’t for the fact that there are other signs of market uneasiness. I pointed to a growing worry among investors about the debt cost. I have also noted the strange shift in the so-called yield curve for interest rates on U.S. debt. If we add a risk premium, it means that the market will seize control over U.S. debt yields and deprive the Treasury of the ability to keep those yields—interest rates—within measured boundaries.

That is another way of saying ‘fiscal crisis’—or, in European parlance, the Greek experience.

Having studied fiscal crises since the early 1990s, I can guarantee that an event like that would be catastrophic for the U.S. economy and, by extension, for the world. Therefore, it is imperative that Congress take the signs of a looming crisis very, very seriously.

Here is how we can identify the emerging risk premium on U.S. debt. We start by comparing U.S. Treasury securities to those issued in a similarly established currency. The best choice is euro-denominated sovereign debt, but not that which has AAA credit rating; if we used that, the differences we see in the market would simply be attributable to the U.S. government having suffered a couple of humiliating credit downgrades.

With the euro-denominated ‘all credit ratings’ debt securities in mind, we single out one of them; using all maturities would create a statistical clutter that does not add information to match the complexity. The debt security of choice is the 10-year note, which is used almost universally as a ‘gauge’ of where a government’s debt is heading in terms of yields and credit status.

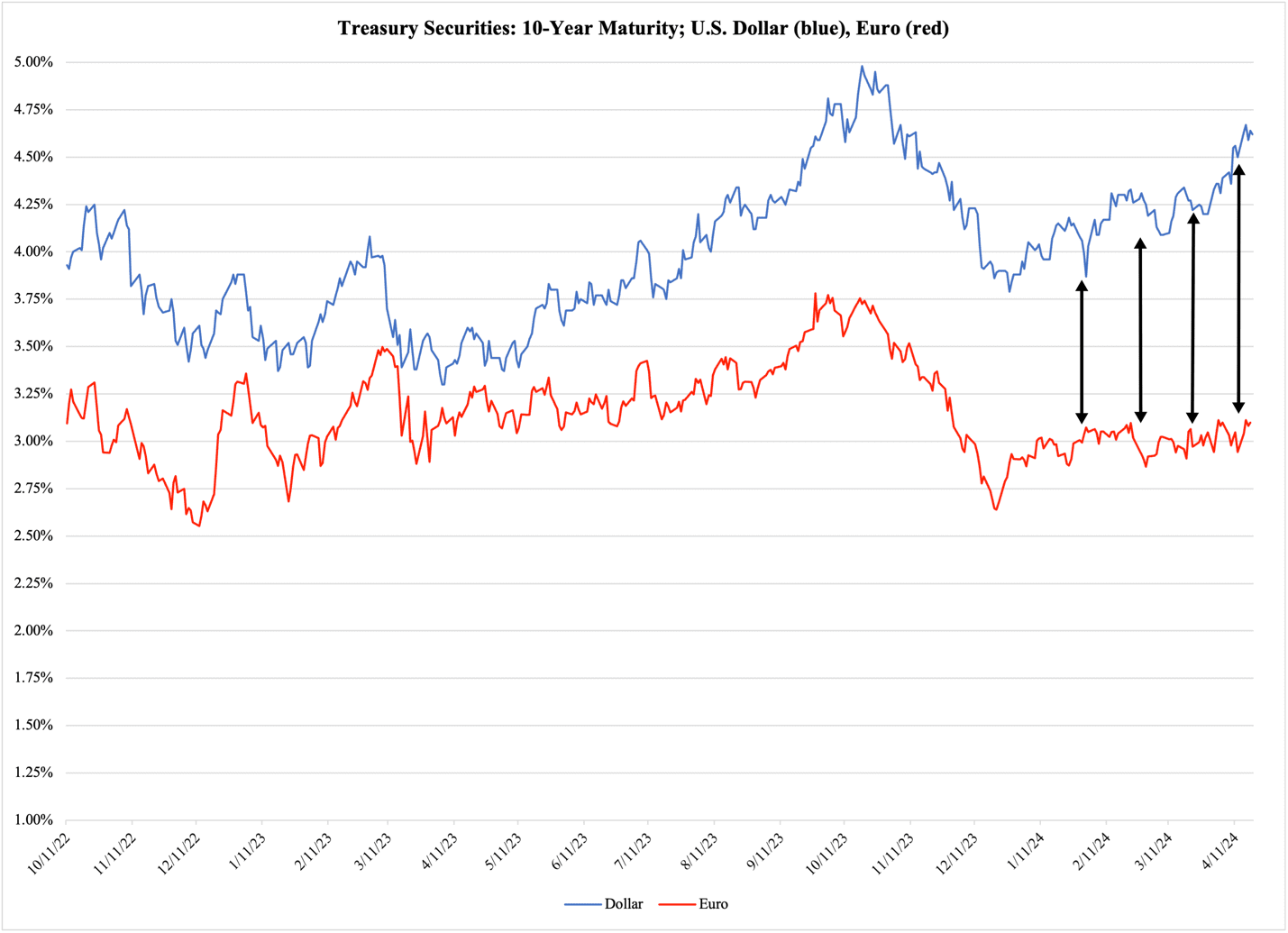

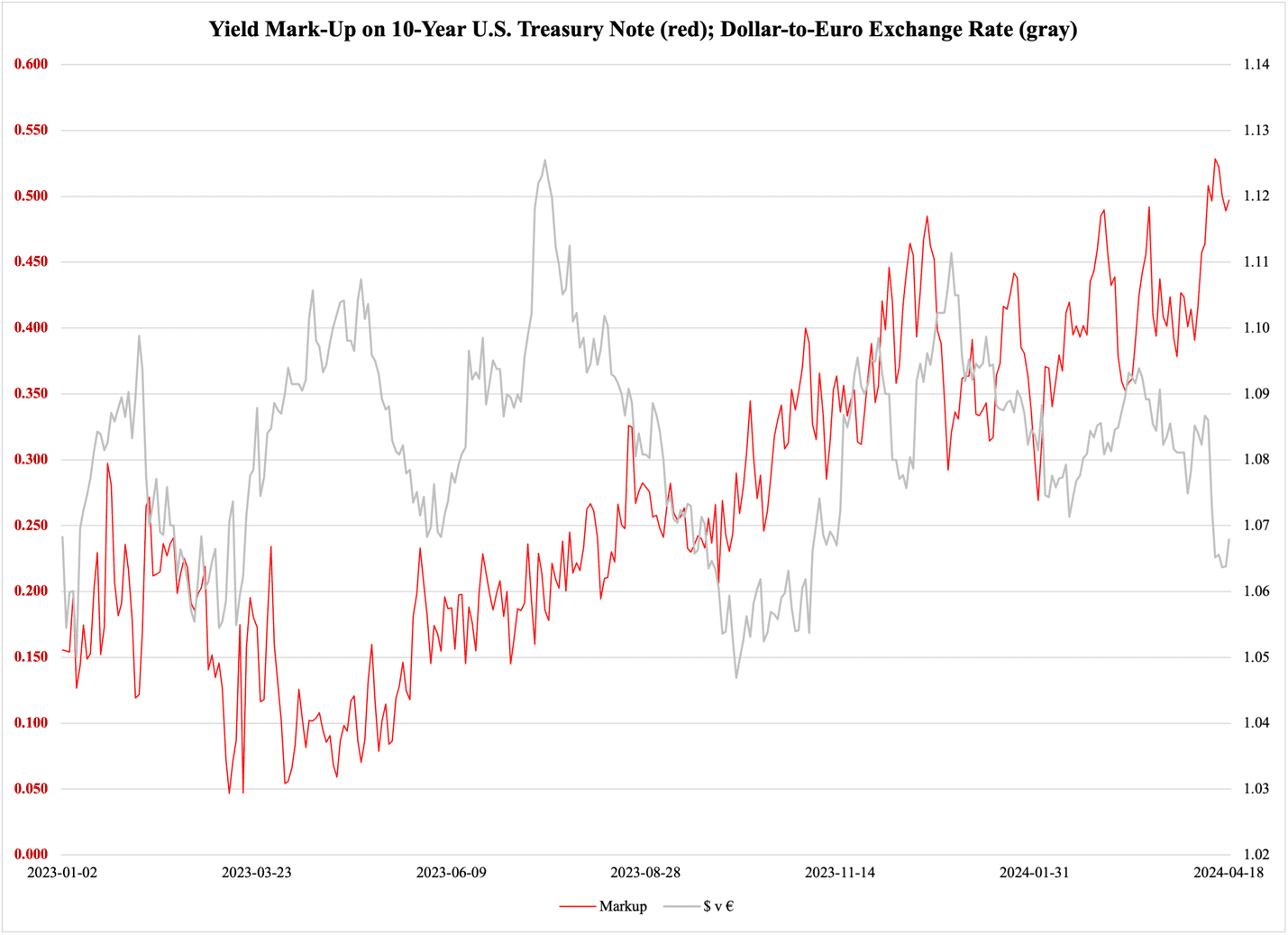

Figure 1 compares the interest rates on U.S. and euro-denominated 10-year Treasury notes. The one issued by the U.S. government (blue) continuously pays better than the equivalent from the euro zone, but the changes up and down in the interest rates are well synchronized. This means that the debt market regards them as generally equal in terms of risk.

However, as the black arrows indicate, this close correlation between the two interest rates weakens with the start of 2024:

Figure 1

The yield on the U.S. 10-year note begins to rise without a similar rise taking place on the euro side.

The astute observer would immediately suggest that this is due to a weakening of the U.S. dollar. If the dollar weakens, it means that a European investor in the American market gets a lower return at any given interest rate, and therefore he demands compensation in the form of a higher return, in this case, interest rate.

Suppose, e.g., that a European portfolio manager buys $100 worth of 10-year U.S. debt. The interest rate is 5%, which means $5 per year. At an exchange rate of $100 per €100, he gets the exact same amount in euros (all other things equal, of course).

Suppose now that the dollar weakens, so that $100 only buys €90. This now means that the $5 interest payment—at 5% on the 10-year note—only returns €4.50. To continue to buy U.S. debt, this investor will now demand that the Treasury in Washington pay a higher interest rate so that his return, on his end, remains €5.

There are many ways to slice this investment strategy. We could include changes in the value of the security itself, as well as opportunities to safeguard returns against exchange rate fluctuations. However, while such technical aspects are valid for large portfolio management operations on the debt market, they do not materially change the underlying principle that a weaker currency forces interest rates upward.

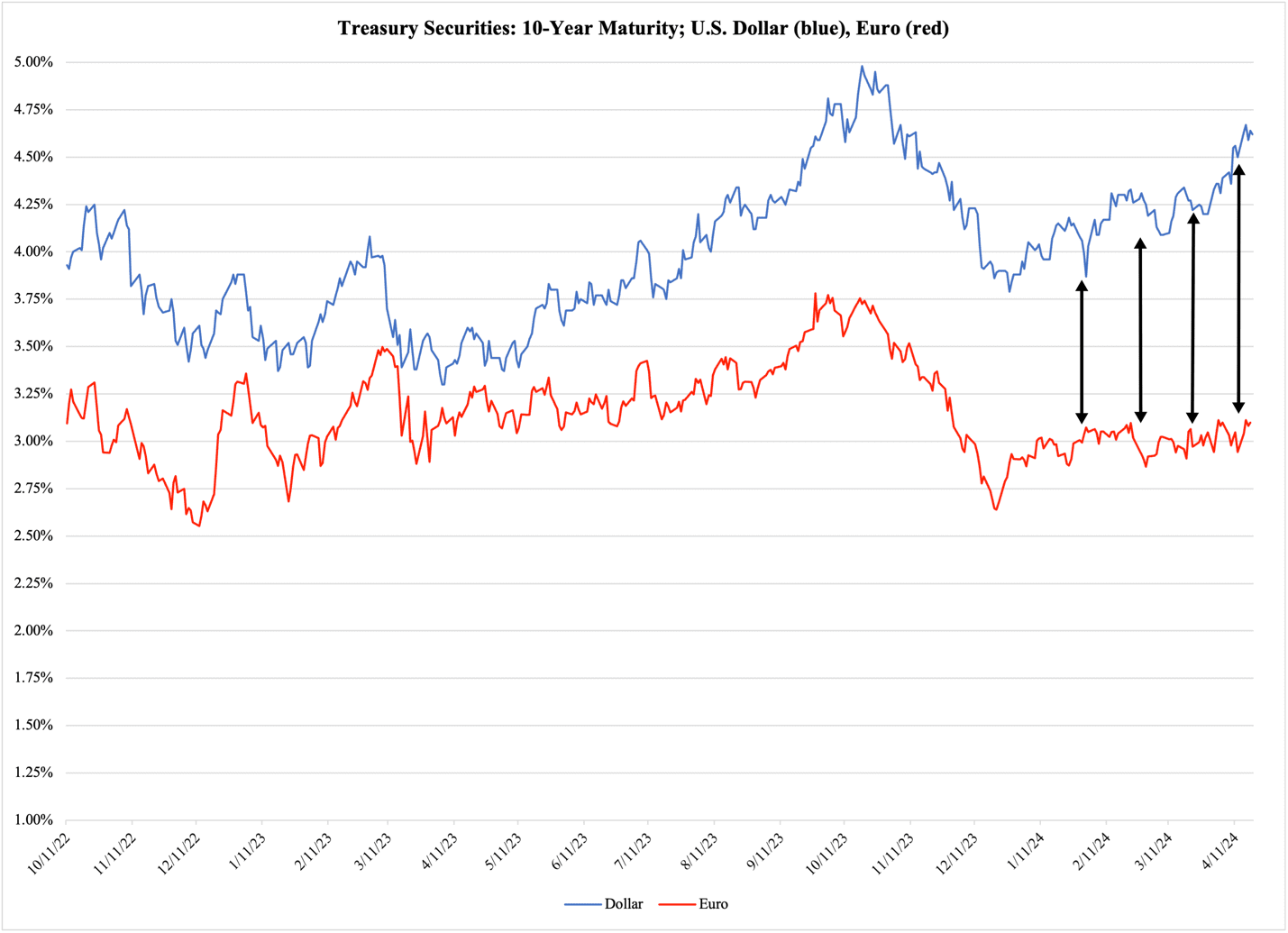

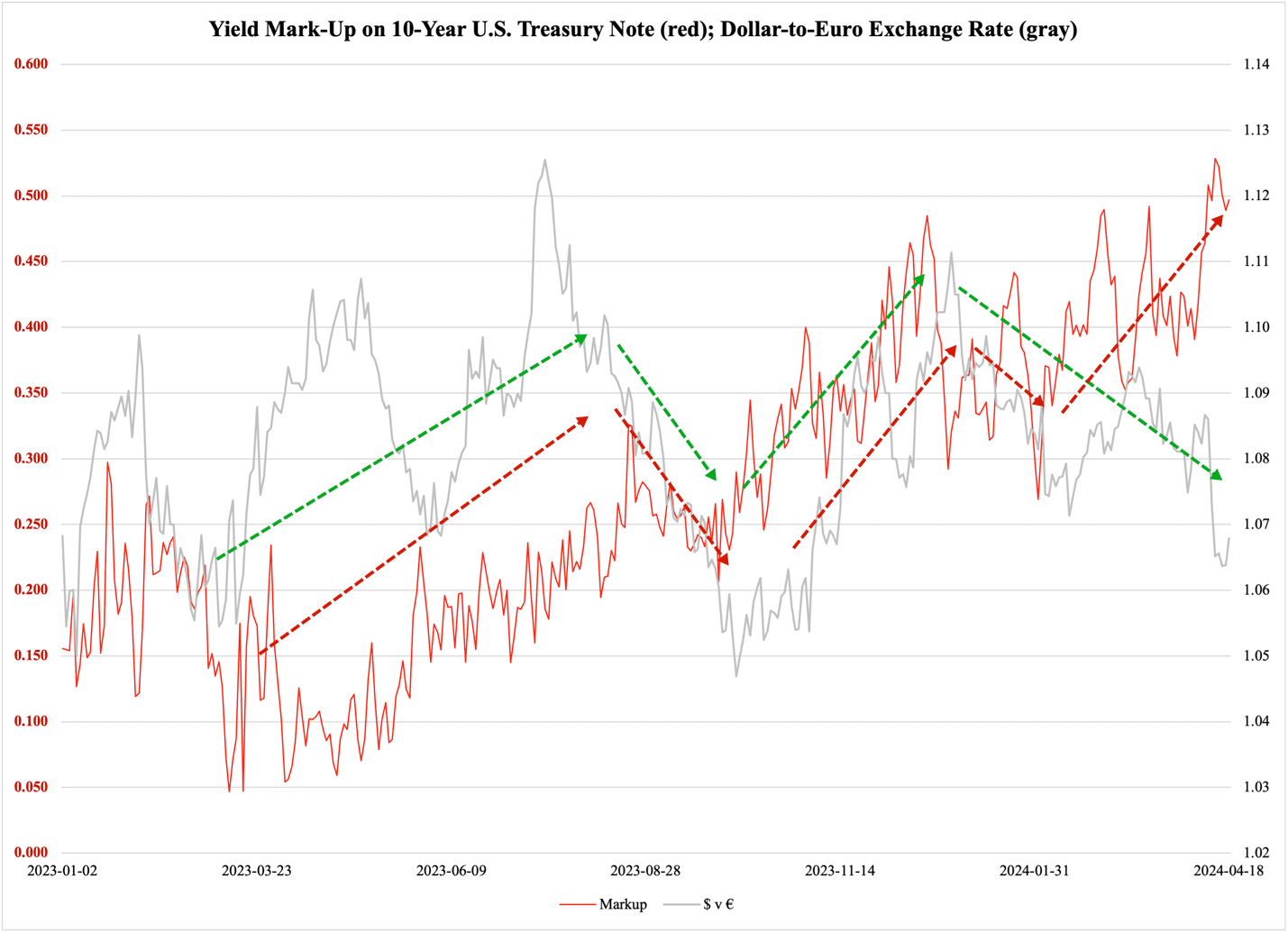

Let us see if the difference in interest rates on the dollar- and euro-denominated 10-year Treasury notes from Figure 1 can be attributed to a weakening dollar. Figure 2a reports the exchange rate between the dollar and the euro (gray line) such that, on the right vertical scale, the value 1.02 means that it takes $1.02 to buy one euro. The higher the value, the weaker the dollar, and vice versa.

On the right vertical axis, we have a ratio that illustrates the mark-up on the U.S. 10-year note compared to the euro-denominated equivalent. The higher the value, the more the U.S. security has to pay per 1% interest on the euro security. As the red line reports, this mark-up has been rising consistently since mid-2023; although it fluctuates quite a bit along the way, the trend is pretty much steady.

It is not quite as easy to identify trends in the exchange rate, but have patience—they are there:

Figure 2a

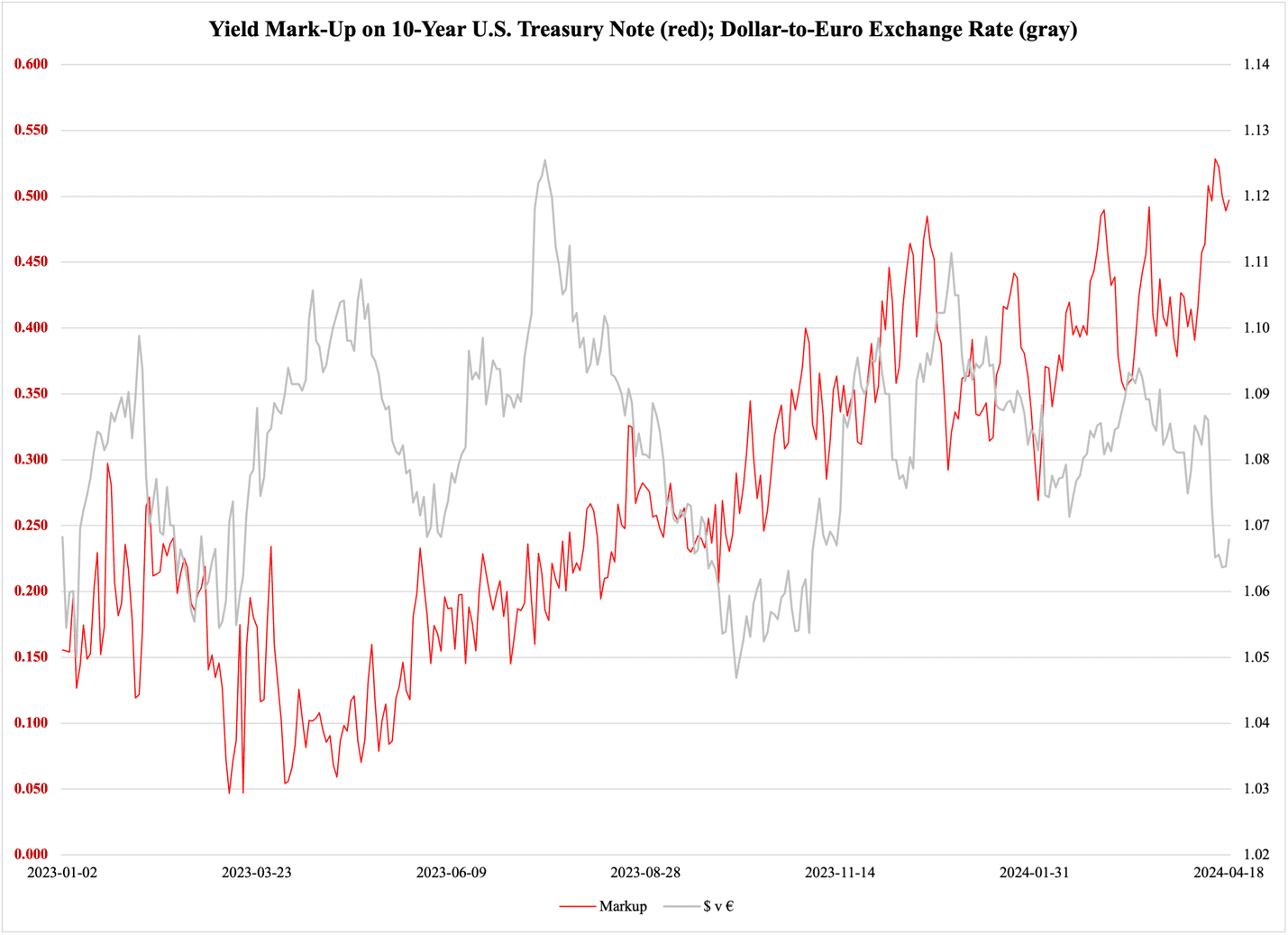

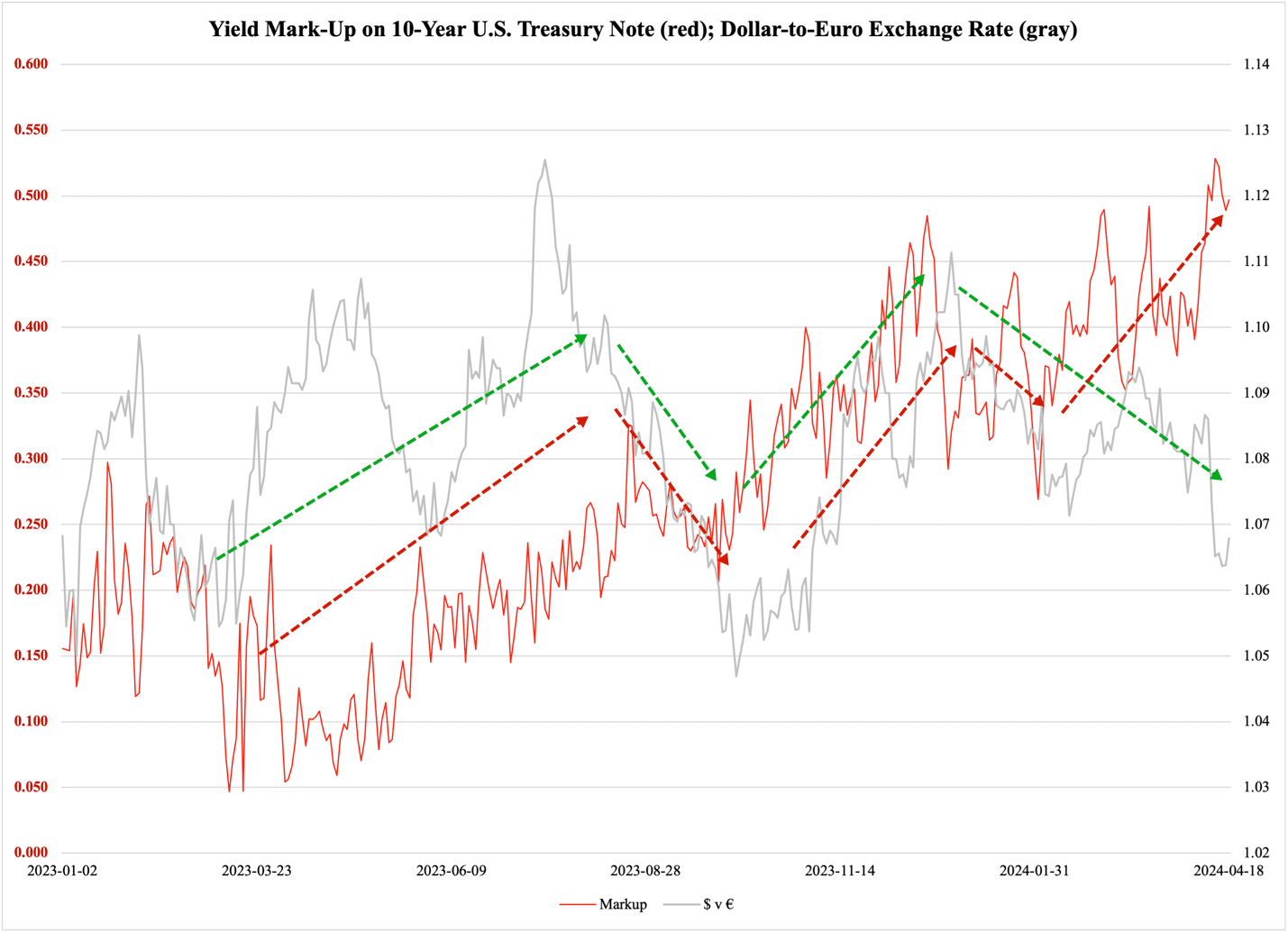

Let us take another look at Figure 2a, in the form of 2b below. We add green arrows for trends in the exchange rate and red arrows for the interest-rate mark-up:

Figure 2b

In the spring and summer of 2023, the U.S. dollar gradually weakens vs. the euro (the green arrow points upward). The trend is characterized by high-amplitude swings, but it is nevertheless a trend. It is accompanied by a similar trend in the yield mark-up, which is entirely expectable.

In the third quarter of 2023, the two trends turn downward, meaning a stronger dollar and a smaller mark-up. This period lasts until approximately the fourth quarter begins, during which the dollar once again weakens and the mark-up rises.

After a brief downtick in the mark-up around New Year, during which the dollar strengthens, the mark-up again turns upward. The dollar, on the other hand, continues to strengthen.

This last, and most recent, episode is the one we should pay attention to. The rise in the mark-up illustrated here is the same as is highlighted in Figure 1. There can, of course, be other factors behind it than an emerging risk premium, but its emergence would nevertheless be perfectly logical given the vocal concerns about the debt that we have heard in the past few months from people in the American financial industry.