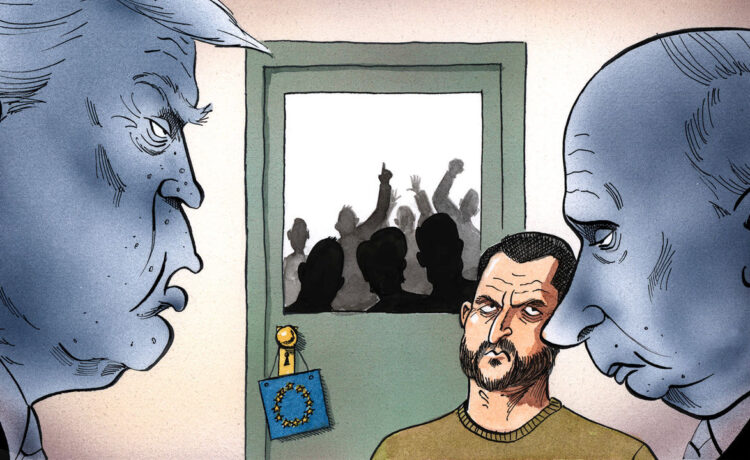

Aside from his gravelly baritone and his attempts at rearranging the world like Tetris pieces, Henry Kissinger is perhaps best known for something he probably never said: that he could never figure out who to call to speak to Europe. A question that was first (not) posed in the rotary-phone era remains unanswered in the age of Zoom. The time for Europe to put forward a single interlocutor for the outside world has come. Soon, under as-yet-unclear circumstances, peace talks over the war in Ukraine may take place. Given what is at stake, Europe desperately—and justifiably—wants a seat at the table. But to be included it will have to put someone up who can stand for photo-ops with Vladimir Putin (representing the interests of his despotic Russian regime) and Donald Trump (representing those of Donald Trump), and perhaps Volodymyr Zelensky (Ukraine). Working out who can’t sit in the European chair, in the eyes of some faction or other, is easy. Coming up with the name of someone who could is tricky.

With 40-odd countries that seldom agree on much, the usual answer is for Europe to send multiple people to represent its interests. That will not be an option this time. For better or for worse (mostly for worse), Mr Trump is the guiding force of the talks, the early throes of which have started—without any input or representation from Ukraine and Europe—in Saudi Arabia. If he chooses to include Europe at all, he is unlikely to give it more than one seat at the table. Ukraine has asked Europe find a single name, but stopped short of saying who it might be.

The least contentious answer might be to turn to the top brass of the European Union. One of its “presidents” (there are many), that of the European Council, is meant to represent the EU at head-of-state level. But nominating António Costa, the newish incumbent, would isolate Britain, a major source of Ukrainian support whose views could hardly be represented by an EU grandee. A former Portuguese prime minister, Mr Costa is a backroom operator by nature. Taking on the envoy job would hinder his day-job chairing meetings of EU leaders, an emergency one of which is planned for March 6th. It does not help that Trumpians hold the EU institutions in contempt, thinking them a supranational deep-state blob ripe for DOGE. This also rules out Ursula von der Leyen, another EU president (of the European Commission).

An obvious candidate for the Euro-mantle would be one of its national leaders. Once the job would have fallen to Angela Merkel, chancellor of Europe’s richest country and broker of its thorniest compromises for over a decade. But it will take months for her probable successor, Friedrich Merz, to cobble together a coalition following elections on February 23rd, and he has lots on his plate.

Europe’s next-biggest country is France. Emmanuel Macron has a strong claim to the Mr Europe job. He dealt with Mr Trump during his first term and in a meeting with him at the White House on February 24th showed there was a decent rapport. Like Russia and America, France is a nuclear-armed power with a permanent seat on the UN Security Council. Mr Macron’s vision that Europe needs “strategic autonomy”, ie, from America, looks prescient given recent events. Political chaos at home paradoxically gives Mr Macron more time to focus on foreign affairs. His major flaw is that hawks in northern and central Europe do not trust him much, least of all on Russia, with which he wanted to open a “strategic dialogue” on security before 2022. Mr Macron has made efforts to engage those countries, and has at times sounded just as hawkish as them—for example by being among the first to suggest that European troops should be sent to Ukraine.

Those who oppose Mr Macron might plump for Donald Tusk, Poland’s prime minister and former president of the European Council. His country grasps the Russian threat acutely; it spends most (as a share of GDP) on defence of any NATO country, which plays well with Trumpians. But Poland has ruled out sending troops to Ukraine, and has a sometimes-tetchy relationship with its leadership. Mr Tusk unwisely disparaged Mr Trump while he was out of office. He shares foreign-policy oversight with the Polish president, who will be replaced in June and might not share Mr Tusk’s views. The Pole has the opposite problem to Mr Macron’s: western Europeans do not want to give their most hawkish member carte blanche to act on their behalf.

What of other big-country leaders? Spain is far from Ukraine and its prime minister, Pedro Sánchez, is not among its most vocal supporters. Sir Keir Starmer thinks Britain can be a “bridge” with America, but Brexit has left it isolated in Europe. Giorgia Meloni is an ideological ally of the American president. But she has yet to resolve how to be both pro-Ukraine and pro-Trump. Sending a respected leader from a smaller country, like Petr Pavel, a retired general turned Czech president, would once have been a typical Euro-compromise. Mr Trump would no doubt start proceedings by belittling the consensus pick. (”Who is this guy anyway?”)

Arise, Mr Europe

Mr Macron appears the sensible choice. He wants the job, and has convened groups of European leaders in Paris already. He made a point of consulting his fellow bigwigs widely ahead of his three-hour chat with Mr Trump this week. Those unsure of his geopolitical instincts could suggest underlings to balance them out. Kaja Kallas, the hawkish Estonian who heads the EU’s foreign-policy arm, would make a fine representative facing the American secretary of state in preparatory talks, say. It is part of Europe’s history and its charm that it cannot easily put forward one person to act for all. But that is the sort of luxury that comes from being primarily a soft power, and these are hard-power times. Europeans must understand that having a single envoy at the negotiating table who flusters some is better than squabbling far away from it. ■