Campaigners say it is still falling millions short, while richer countries have just missed a deadline for the new loss and damage fund.

Ireland is set to meet its pledge of providing €225 million in climate finance per year to poorer nations by 2025.

Tánaiste (deputy prime minister of the Republic) Micheál Martin shared the positive news with the publication of Ireland’s climate and environmental finance report for 2022.

It’s a rare bit of punctuality from developed countries, which have long disappointed developing nations on this front. They failed to meet their promise of $100 billion (€91.8bn) climate finance annually by 2020 and until 2025 – and it’s still a contested issue whether this has now been met.

These richer countries are again under fire for missing an important deadline concerning the loss and damage fund – a subset of climate finance which effectively compensates climate-damaged countries.

Developed countries failed to choose their representatives on the board of the new fund by the agreed deadline of 31 January. This risks a delay in channelling the funding to the world’s most vulnerable communities.

Ireland’s government appears to recognise the urgency of honouring climate finance commitments.

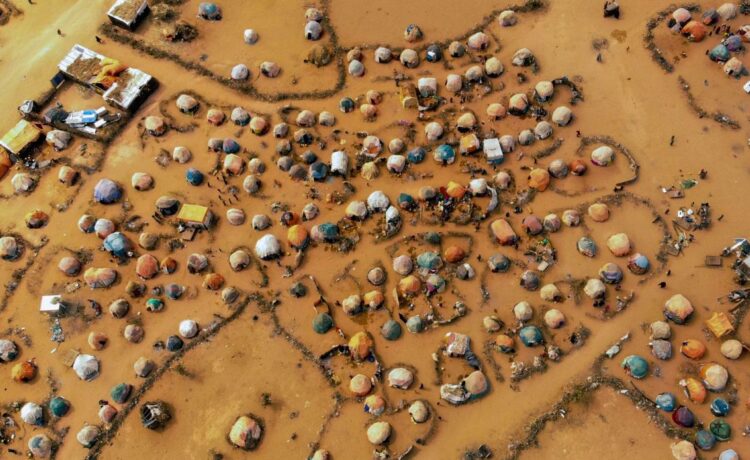

“Last year was the hottest ever on record,” says Martin. “The wildfires, droughts and flash flooding that affected millions across the world have brought home the brutal realities of climate change. Countries and communities who have done the least to bring about this crisis are the ones hit hardest by its impacts.”

How is Ireland delivering on climate finance?

Ireland’s new report from the Department of Foreign Affairs (DFA) shows it provided €120.8 million in climate finance to developing countries in 2022 – a 21 per cent increase from 2021.

Ireland’s climate finance has more than doubled since 2015 and will grow further in the years ahead, says Minister of State for International Development and Diaspora, Sean Fleming.

“This report demonstrates our commitment to reaching the furthest behind first and to channelling support to those most at risk of being left behind as a result of the climate crisis.”

Irish Aid, the government’s official development assistance programme, has identified climate change as one of its four priority areas. Funding for the climate finance pot comes primarily from the DFA (responsible for 65 per cent), as well as the Department of Finance, the Department of the Environment, Climate and Communications, and (to a lesser degree) the Department of Agriculture and Fisheries.

80 per cent of the funding is earmarked for adaptation in developing countries – enabling them to respond to the inevitable and potentially devastating impacts of climate change.

At COP28, Tánaiste Martin announced €50m of new funding, with €6 million specifically for Small Island Development States (SIDS) – whom he described as “being in a battle for survival.” He also stated with confidence that Ireland would meet its €225 million annual commitment by 2025.

The country has another eye on its own adaptation needs. Last month Ireland published its first climate change assessment report, which provides a strikingly detailed picture of how the island is increasingly vulnerable to extreme weather events, sea level rise and coastal erosion.

Is €225 million a year a fair contribution from Ireland?

Trócaire, the official overseas development agency of the Catholic Church in Ireland, welcomed the new report, but says Ireland is still falling short of its fair share of climate finance.

“It’s really positive to see an upward trajectory in the figures,” Siobhán Curran, head of policy and advocacy at the humanitarian organisation, tells Euronews Green. “[But] we really think Ireland, along with other richer countries, needs to massively scale up the climate finance to pay our ecological debt.”

According to analysis by the Overseas Development Institute (ODI) think tank, Ireland’s actual fair share of the $100bn sum is approximately €500 million. It’s in a relatively poor performing group of Annex II countries, also including Spain and Portugal in Europe. ODI’s 2023 calculations put Norway at the top and Greece at the bottom of the pile.

“We’re calling on Ireland to really drastically scale up its climate finance in scale with needs,” says Curran. Trócaire works in a number of climate-hit countries, including Malawi, where more than half a million people were displaced by Cyclone Freddie last year.

Though Ireland has a way to go on volume, Curran praised its focus on adaptation – where many other European countries are providing finance too skewed towards mitigation. It also does well to provide climate financing in the form of grants rather than loans, which risk pushing poorer countries further into debt.

Developing countries have missed a loss and damage fund deadline

Climate finance permeated discussions at COP28, though the summit did not produce any major developments on this front beyond the creation of the new loss and damage fund.

Nonetheless, a new report from the High Expert Group on Climate Finance launched at the start of the summit, underscores how intertwined climate action and financial support is.

“The world is badly off track on the Paris goals, as the first global stocktake shows, the primary reason for which is insufficient investment in key areas, particularly in EMDCs [emerging markets and developing countries],” the group, chaired by leading economists Vera Songwe and Nicholas Stern concluded.

In Dubai, governments asked the UN’s climate change arm to arrange a meeting of the fund’s new board “once all voting member nominations have been submitted, but no later than 31 January 2024”.

However as the deadline passed this week, developed nation groups had chosen none of their reps, while developing countries had selected 13 of their 14, Climate Home News reports.

“There is some concern that we’re losing a bit of time given that we have quite a bit that would need to be discussed,” said Fijian climate ambassador Daniel Lund.

The UK-based news site reports that a disagreement between two major blocs, the EU and the ‘Umbrella Group’ – which includes the US, Japan and the UK – could be slowing matters down.

The blocs are reportedly clashing over how many seats each should get, with the EU arguing it should be allocated more since it has pledged notably more money to the fund: $447m (€411) compared to the Umbrella Group’s $115m (€106m).

Climate finance is shaping up to be the biggest agenda item at COP29 next year in Azerbaijan.

This is because countries have to agree on a post-2025 climate finance goal to replace the previous $100bn (€91.8bn) pledge. This new collective quantified goal (NCQG) as it is termed, underscores the urgent needs to scale up funding, Trócaire’s Curran adds.

“We’re going to see that the climate finance need is much bigger than what’s being paid,” she says.

In Ireland, as in other richer countries, “we need to look at new sources, including options such as aviation taxes, shipping levies, taxes on fossil fuel companies and wealth taxes.”