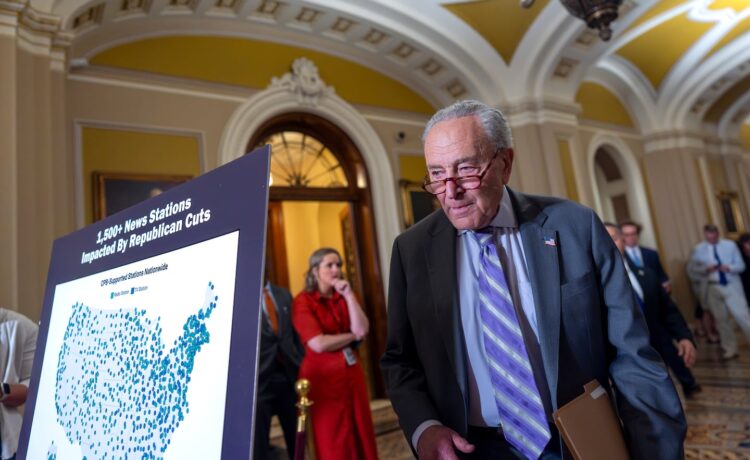

WERU is one of about 1,500 public broadcasters nationwide bracing for severe budget cuts, following a Senate vote on Thursday morning to claw back $1.1 billion in funding to the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, a major source of funding for local public media. The legislation is expected to be approved by the House before going to President Trump, who is expected to sign it.

Murphy said money from Corporation for Public Broadcasting helps cover the costs of electricity, equipment, and buying national programming. WERU is now turning to its 2,000 members and other listeners to help fill the funding gap and keep the station operating.

“My big hope is that people who are listening who don’t usually give will say, ‘You know, now is the time for me to start giving,’” he said. “We are determined that our station and community radio network will keep going in some form or another.”

In Provincetown, another small station, WOMR, faces the loss of 15 percent of its revenues. It is looking to other sources of money, such as family foundations and fundraisers.

“We’re not cutting anything,” the station’s executive director John Braden said. “I think it will be rough at first, but we will settle into a groove that will work out.”

Vijay Singh, chief executive of Vermont Public, said the company foresees potential staffing or programming cuts in their radio and television department, despite relatively high volume of audience donations.

“This is a really tough time, for the system, Vermont Public, and our audience,” Singh said. “I feel for all Americans that if this goes through, we will lose a crucial service to our democracy.”

Public broadcasting offers free access to news, local information, independent music, and emergency alerts. As local newspapers continue to close and news deserts expand, public media sometimes serves as the only source of news in rural areas.

Across the country, about 120 rural stations rely on federal funding for at least 25 percent of their budget, while 33 stations rely on federal funding for more than 50 percent. Many of these are tribal stations operated for Native American communities — where cable or internet access is spotty — and won’t survive without funding.

Rima Dael, the chief executive of the National Federation of Community Broadcasters, a nonprofit that supports and advocates for small local stations, estimates that 30 to 50 stations will have to shut down within a year of the bill’s signing.

About two-thirds of NFCB’s members are stations in rural regions. More than half operate on budgets of $100,000 or less. All stations rely on Corporation for Public Broadcasting funding.

“The draconian cuts being made across the board is really a misunderstanding of how [public media systems] in our country need to be supported,” Dael said.

Federal funding is determined by calculations of the population a station serves and whether it can rely primarily on donations from listeners. Stations in New England are likely to keep the lights on, but the public media landscape will become increasingly more expensive.

Local stations affiliated with NPR and PBS are required to pay membership dues and buy national programming to air locally. As stations shut down nationwide, those that remain will need to pick up bigger shares of the cost of shared resources used, such as satellite service.

Pam Johnston, CEO of Rhode Island PBS and its radio affiliate, The Public’s Radio, said the broadcaster will lose nearly $1.1 million in federal support, or about 10 percent of its budget.

That money “fuels the local journalism and educational programming that our community depends on,” she said in a statement. “The looming loss does not change our public service mission; nor does it reduce the demand for the kinds of informational, educational, and cultural programs we produce or the civic engagement we provide.”

The largest public broadcasters in the region, GBH, an NPR and PBS affiliate that produces national programs such as NOVA and Frontline, and WBUR, another NPR affiliate, will also take a hit, potentially affecting their programming and prompting layoffs.

GBH laid off 6 percent in June, and WBUR let go of 14 percent of its staff in April of 2024.

GBH’s chief executive, Susan Goldberg, estimated the broadcaster will lose $16 million, or about 8 percent of its funding. She said the company is coordinating with PBS, NPR, and the Corporation for Public Broadcasting to assess next steps.

“Although these are uncertain times, GBH has a long history of innovation and we’ve been a public media leader for nearly 75 years,” Goldberg said in a statement. “We’ll continue to evolve, creating high-quality content, reaching new audiences, and meeting the needs of our community.”

Yogev Toby can be reached at [email protected].