As President Donald Trump seeks to shut down the U.S. Department of Education, some of Louisiana’s top education officials say they are eager to bid the agency adieu.

Echoing Republicans who have long opposed the Cabinet-level federal agency’s existence, Louisiana education leaders see the department as inefficient and an example of federal overreach, arguing that school policies should be left to states and local communities.

“I have always suggested that the department should not exist,” Louisiana Superintendent of Education Cade Brumley said in an interview Thursday. “I trust people in Louisiana to make decisions based on the educational needs of the state of Louisiana.”

Cade Brumley, the Louisiana state superintendent of education, speaks with state and local administrators and educators during a school visit Monday, February 10, 2025, at David Thibodaux STEM Magnet Academy in Lafayette, La.

After repeatedly calling for the Education Department’s elimination, reports this week said Trump is preparing to issue an executive order instructing his newly confirmed education secretary, Linda McMahon, to shut down the agency. In an interview Friday, McMahon said Trump “certainly intends” to sign an order, but did not say when.

Abolishing the department and shifting some of its functions to other agencies could reduce federal oversight and regulation of schools.

That scenario would be cheered by some of Louisiana’s Republican leaders, who often clashed with the Education Department when it was controlled by President Joe Biden, a Democrat. Last year, the state sued to block an agency rule that barred discrimination against LGBTQ+ students, saying it conflicted with Louisiana laws and values.

Ronnie Morris, president of Louisiana’s state board of education, said he would welcome the department’s demise.

“The idea is to reduce the bureaucracy and give the states more control,” he said Friday.

But some education advocates say that federal oversight is an essential safeguard for students who have often been underserved by public schools, including low-income students, students of color and those with disabilities.

“The idea of closing the Department of Education without a plan to support students is really a devastating idea,” said Halley Potter, director of pre-K-12 education policy at The Century Foundation, a left-leaning think tank. “I would expect that it would worsen student outcomes and move us in the wrong direction.”

Money for schools, with strings attached

The U.S. Education Department, which was created by Congress under President Jimmy Carter in 1979, has limited power over what’s taught in schools, as those decisions are left to states and local school boards. Most funding comes from local sources as well.

Still, dismantling the agency, which has more than 4,000 employees, could have a big impact on Louisiana schools.

The department doles out billions of dollars in federal aid to schools and colleges annually, including about $18 billion to support students from low-income families and $15 billion for special education, and it manages some $1.5 trillion in federal student loans. It also tracks education data and enforces laws that protect students, such as Title IX, which prohibits sex-based discrimination at schools and colleges.

Students look over the homeroom list in the quad of the renovated Baker High School on the first day of classes on Monday, August 12, 2024 in Baker, Louisiana.

The department and many of its functions were established by federal law and would require Congressional action to change. If lawmakers agreed to shut down the department, McMahon said its essential operations could be assigned to other agencies. For example, the Department of Health and Human Services could take over enforcement of the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act, or IDEA, which requires public schools to meet the needs of students with disabilities.

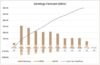

Louisiana relies heavily on federal education dollars.

The state received about $2.3 billion from federal sources for K-12 schools in 2021-22, the most recent year available. That represents about 19.5% of its school funding — one of the highest rates in the U.S., where about 14% of public education funding flows from the federal government. Much of the money comes through Title I, a program that supports schools with large shares of students from low-income families.

“The states that have the highest percentage of federal funding, a lot of which is coming from Title I, they are largely red states,” Potter said. “And Louisiana is high up on that list.”

The Education Department’s control of federal funds is its main source of power. It can set conditions for schools to receive the money or threaten to withhold it from schools or universities that violate federal laws.

For instance, under the Biden administration, the department put new restrictions on funding for charter schools. In 2022, when Louisiana Gov. Jeff Landry was the state attorney general, he joined other states in challenging the regulations.

Under the current Trump administration, the department cut $600 million in grants to teacher-training programs, including several in Louisiana, claiming they promoted “divisive ideologies” related to race. On Friday, the department and other federal agencies said they would cancel $400 million in grants and contracts to Columbia University because they said the school failed to adequately address antisemitism on campus.

If the department is dismantled, school funding could come with fewer restrictions. Some conservative groups have called for converting programs like Title I, which requires the funding to go to hiring teachers and counselors or other approved ways to support low-income students, into block grants that let states decide how to spend the money.

Students arrive for the first day of school at Arthur Ashe Wednesday, August 7, 2024 in New Orleans. (Staff photo by John McCusker, The Times-Picayune | NOLA.com)

Advocates like Potter said such a change would risk diverting funds from schools that need them most.

“Without any kinds of guardrails and accountability,” she said, “it could be misspent on things that aren’t related to instruction and aren’t directly helping the students it’s designed to help.”

Pointing to students’ recent reading improvements, Brumley said Louisiana knows better than federal bureaucrats what support students needs.

“We’ve proven we have the ability to make good decisions on behalf of kids and families and communities,” he said. “I think that given additional flexibility and fewer strings, we can do more of that.”

Protecting students

The Education Department is also the chief enforcer of federal education laws, including IDEA and Title IX.

States sometimes bristle at the oversight.

Last year, Louisiana and 25 other Republican-led states took the department to court after it issued a rule saying that Title IX also bars discrimination based on sexual orientation and gender identity. Brumley advised schools to disregard the federal rule, saying it conflicted with a state law banning transgender students from participating in women’s sports.

“That really infringed on the sovereignty of the state,” he said Thursday.

Cade Brumley, the Louisiana state superintendent of education, speaks with Principal Sherri Livesay during a school visit Monday, February 10, 2025, at David Thibodaux STEM Magnet Academy in Lafayette, La.

The department’s Office for Civil Rights also investigates complaints filed by students, parents and advocates.

The office has dozens of open investigations into Louisiana schools and colleges based on complaints of discrimination against students based on their race, sex, national origin or disability, according to the office’s public database.

In 2023, the office launched an investigation into the Jefferson Parish school system following a complaint that the district’s decision to close several schools disproportionately affected Black and Latino students and students with disabilities. The district said it was cooperating with the Education Department, and said the allegations lacked merit.

The complaint system “is a way to get districts to make sure no federal rights are being violated and, if they are, to make sure they’re remedied,” said Lauren Winkler, a senior staff attorney at the Southern Poverty Law Center, the legal advocacy group that filed the complaint.

At her confirmation hearing last month, McMahon said the Office for Civil Rights could be moved to the Justice Department.

Critics say the move would shift the complaint system to the courts, which would slow down the process.

“Federal civil rights law is a difficult area to litigate,” Winkler said.

But Louisiana officials say that, whatever form federal oversight takes, the state will take care of its students.

“I think we’re going to fight for the needs and best interests of all our students,” said Morris, the state board of education president.