A lot of leading hedge funds are fans of the US Treasury “basis trade”. And it’s easy to see why: this savvy, uncomplicated strategy allows them to snag some seemingly straightforward returns. But don’t let the simplicity fool you: all the major financial watchdogs from the International Monetary Fund to the Bank of International Settlements to US federal regulators are waving red flags about its potential risks. Here’s what you need to know.

First, what’s the basis trade?

It’s pretty simple, really. In theory, the price of actual cash bonds and the futures on those bonds should match. But in the real world, they rarely do – at least not at first. And the gap between the two prices opens the door for hedge funds and other big players to rake in some “risk-free” profits – in theory, at least. Here’s how they do it:

First, they spot the opportunity. Hedge funds keep an eye out for when the futures price of a Treasury bond is higher than its current cash price. This difference might pop up because of a huge demand for bond futures or an influx of actual bonds in the market.

Then, they make the trade. These players will buy the undervalued cash bonds and sell the overpriced bond futures. Since the price gap is slim, they need to deal in big bucks to make the play worth it. But – here’s the kicker – they don’t use much of their own money in the trade. Thanks to the magic of repo markets (think of this as a pawn shop for traders), they can borrow most of the purchase price, using the bonds as collateral. So, on a $500 million bond buy, they might front as little as $10 million of their own cash. That’s some serious leverage.

Next, they manage their position. They’ll hold onto the bonds they snapped up bonds with borrowed money, keeping a watchful eye on their future short. And every day, they’ll pay a bit of interest on the borrowed money, which is just part of the game.

Finally, they’ll exit the trade. If the prices eventually align the way they should (i.e. if they converge), they’ll sell off the bonds and buy back the future contract, pocketing the difference, minus any borrowing costs and fees. On the other hand, if things start to look dicey, they can quickly liquidate the trade by selling off the bond and closing out the future to avoid bigger losses.

In theory, it’s a risk-free “arbitrage” opportunity for the hedge fund: the futures price will eventually converge to the spot price, and the hedge fund will pocket the profit.

So why would regulators have a problem with this?

Under normal conditions, these kinds of trades get a thumbs-up from regulators because all that buying and selling helps keep the markets liquid and efficient, syncing up the cash and futures markets. But when markets don’t behave very normally, things can get dicey.

Remember, for these trades to work, hedge funds need a smoothly running repo market that gives them easy-to-access leverage, plenty of liquidity in both bonds and futures so they can move easily in and out of positions, and low repo rates to ensure that the cost of borrowing doesn’t eat up all their profits.

And when these conditions falter, the stability of the basis trade does too, ringing alarm bells for financial regulators. Here’s why:

Lots of things can lead to a spike in repo rates – for example, moves from the Federal Reserve (the Fed) aimed at slowing the economy by decreasing the amount of liquidity, a sudden demand for cash among financial institutions, foreign central banks selling their Treasuries all at once, or a sharp rise in credit risk.

When repo rates – which, of course, are a critical cost factor in basis trades – surge, the strategy can quickly become unprofitable. And because hedge funds are often heavily leveraged, they may find themselves hemorrhaging money as a result, leaving them with little choice but to liquidate their positions, and fast. That kind of mass selloff can put heavy downward pressure on bond market liquidity as other investors, sensing trouble, start to offload their Treasuries, exacerbating the problem by thinning the pool of buyers.

In a worst-case scenario, such pressures could put major hedge funds in jeopardy, especially those that have become pivotal to the functioning of the Treasury and repo markets. And their struggles could ripple through the broader financial system because of the interconnected nature of its participants. If these significant investors start to fail, that could have an unsettling effect on other market players and other assets (which they might have to sell to raise funds to meet margin calls).

This scenario isn’t hypothetical: it’s what nearly happened during the pandemic, when a spike in the repo rates prompted funds to unwind their basis trades, sparking liquidity worries in the most important market – the short-term bond market – and prompting an intervention from the Fed.

Should this worry you?

Well, the good news is that the situation seems better now than it was during the pandemic: repo markets are more liquid, there’s less leverage in the system, and market participants are more aware of the risks. What’s more, recent research from the Fed shows that the total value in the trade might be lower than initially thought. And get this: by mid-2026, all repo-financed Treasury deals will have to go through a central clearinghouse, which should clip the risk wings of this high-flying trade.

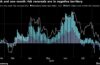

But that doesn’t mean everything will be smooth sailing. With interest rates on the rise lately and a ballooning supply of bonds being issued to cover growing government deficits, that tricky basis trade has been making a sneaky comeback. And with the Fed possibly tightening liquidity and various stress triggers looming in the bond markets, the repo market could face a real test soon.

History is littered with financial mishaps stemming from all-too-familiar issues: excessive leverage, opaque operations, concentrated investments, a scene dominated by just a few big players, and an overreliance on stable market conditions. From the global financial crisis, to the bond market stress of the pandemic era, to the near collapse of pension funds in the UK, to the dramatic failures of highly levered firms like LTCM and Archegos – it’s clear how quickly the banking system’s pipes can burst under pressure, particularly when huge, levered, murky money entities are involved.

These messes are each a stark reminder that, even with today’s stronger regulations and more resilient financial structures, you should never underestimate potential risks, especially in a time of rising uncertainty. So keep your guard up and make sure your portfolio can handle the potential volatility. You know, just in case.