China’s economy and stock market have fallen off their peak but still pose a conundrum for investors. They can invest in broad, diversified emerging-markets funds with their still huge China stakes and bear the country’s substantial economic and geopolitical risks, along with the vicissitudes of other developing markets. Or investors could try to cobble together collections of various regional funds that underweight the world’s second-largest economy and one of its biggest stock markets, risking a bad case of FOMO if China rebounds and takes off in ensuing years.

Asset-management firms, which rarely miss a chance to devise fee-collecting solutions to such problems, in recent years have offered more emerging-markets funds that simply carve out China. Ostensibly, such funds give investors, advisors, and institutions more control over their helpings of China in the emerging-markets portions of their portfolios or the ability to skip the Middle Kingdom altogether. By mitigating one big risk, though, emerging-markets ex China funds may be courting others.

Here’s a look at this relatively new, unofficial subcategory of emerging-markets strategies.

The Conundrum

In 2010, China leapfrogged India, Japan, and Germany to become the world’s second-largest economy. Over the next 10 years, its weighting in the MSCI Emerging Markets Index rose from 17.4% to an all-time high of 42.8% in October 2020. Slowing economic growth and a retreating stock market reduced that stake to 26.1% by the end of 2023, but China remained the index’s largest single country.

Some investors aren’t comfortable having so much money in China, given its murky property market, challenging demographics, and penchant for intervening in the affairs of its largest public companies.

The Answer?

To accommodate wary emerging-markets investors, fund companies have launched 16 emerging-markets ex China funds since 2021, bringing the total to 21. How do these funds differ from the typical diversified emerging-markets Morningstar Category peer?

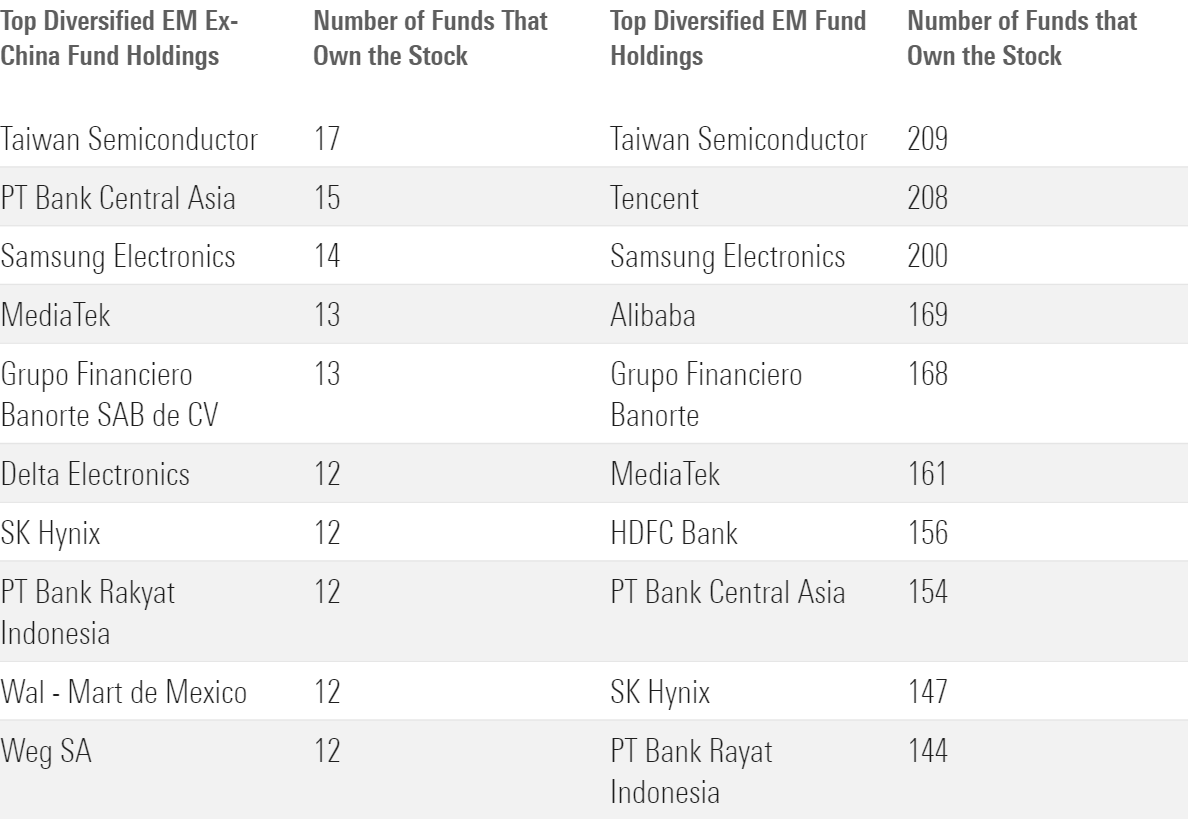

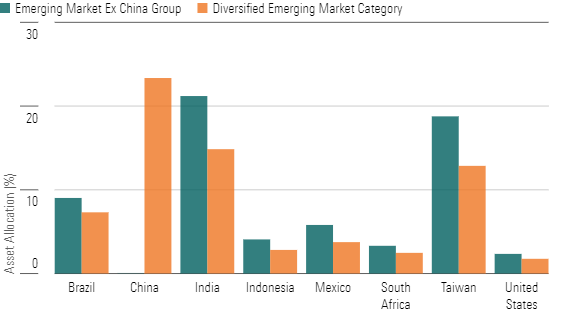

The first difference is these portfolios tend to own more of other developing countries such as India and Taiwan, which aren’t exactly free from China-related risks. India, a democracy, and China, a communist country, are rivals, and the Chinese government and military openly plot and maneuver to make Taiwan part of the mainland again. Some of emerging-markets ex China funds’ most popular holders include Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing TSM, PT Bank Central Asia BBCA, and Samsung Electronics SMSD. Taiwan Semiconductor is often a top holding among diversified emerging-markets funds, which also own big Chinese companies such as Tencent TCHY, Alibaba BABA, and Meituan.

Emerging-markets ex China funds tend to have more exposure to Brazil and Mexico, which have their own economic, social, and political downsides. Both countries have been accused of having corrupt governments, which have led to political uprisings.

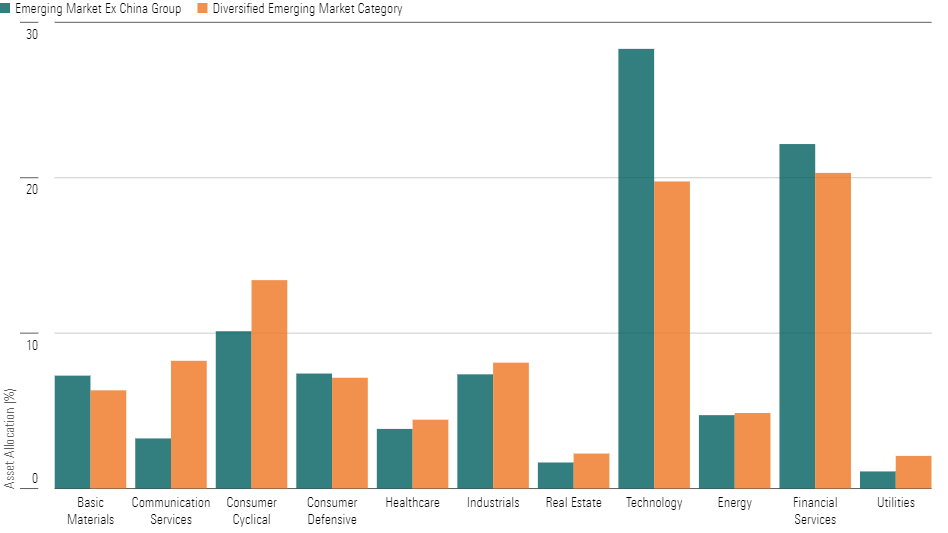

Emerging-markets ex China funds also tend to own fewer consumer cyclical companies because they take a pass on Chinese giants such as Alibaba, Meituan, and Tencent. As a result, these funds tend to have more money in technology, financial services, and basic materials firms. Indeed, the typical emerging-markets ex China fund has close to half its assets in technology and financial stocks, which courts sector risk.

The Response

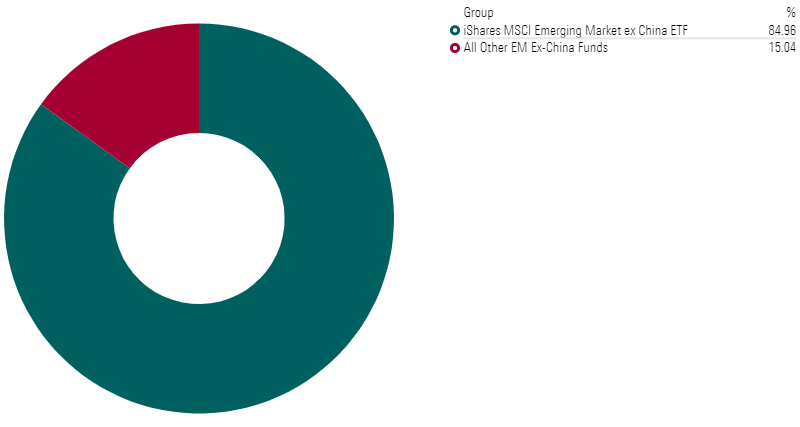

These funds are still new, but they have attracted flows. In 2023, emerging-markets ex China funds took in $5.6 billion. IShares MSCI Emerging Markets ex China ETF EMXC, which in 2023 took in $4.8 billion (about 82% of the group’s flows), was the most popular choice.

The timing of the funds’ launches has made them look good. In 2023, Chinese equities were among the globe’s worst-performing stocks. The average emerging-markets ex China fund gained 21.8% in 2023, which was far more than the typical diversified emerging-markets category peer’s 12.0% gain. Moreover, all 15 of the funds with full-year 2023 returns ranked in the top quintile among its category peers.

The average emerging-markets ex China fund also is a little cheaper than the average diversified emerging-markets category fund. That’s because seven of the 21 funds available are exchange-traded funds, which tend to have lower expense ratios than traditional mutual funds.

Will They Last?

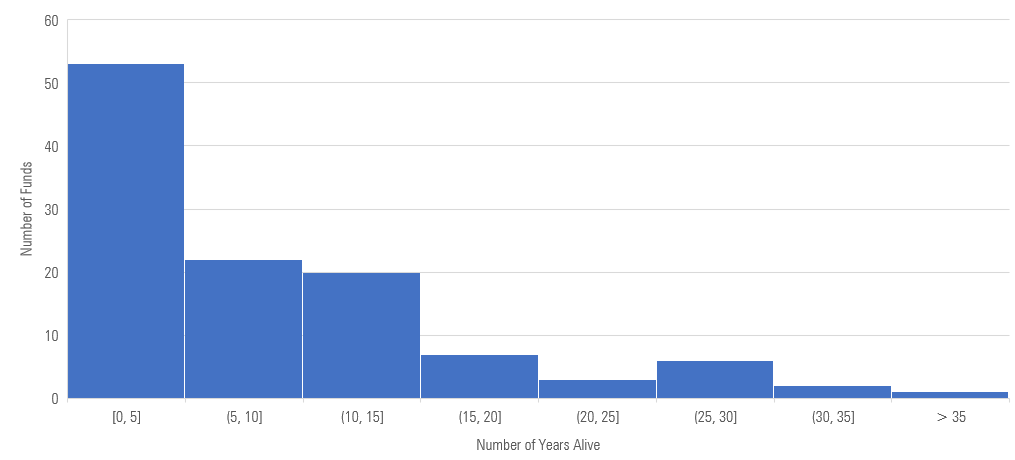

It’s not clear whether these funds are just another flash in the pan or if they’re here to stay. If history is any guide, there could be a shakeout. Japan has long posed a similar problem for the MSCI EAFE Index and funds that use it as a benchmark; the island nation currently makes up nearly a fourth of the benchmark and has taken up more in the past. Since the first launch of an Asia ex Japan fund in 1977, asset managers have launched 114 such funds in the United States. As of December 2023, just 25 remained. In fact, nearly half the Asia ex Japan funds didn’t make it to their fifth birthday.

Are They Worth It?

Emerging-markets ex China funds help solve some problems but create others. On one hand, they allow investors to minimize or eliminate China exposure, but they increase helpings in other developing markets with their own issues. Not only is this risky, but investors must consider how much, if any, China exposure they want, which can complicate portfolio management and leave a wider margin for error. Only time will tell whether allocating nearly a fourth of emerging-markets assets in China proves to be a good idea, but it’s also risky to go against the wisdom of the markets. If history is any indication, investors should approach these funds with a healthy dose of skepticism.