The U.S. government has published its five-year strategy for using CHIPS Act funds to bolster the American semiconductor industry. The 61-page paper (PDF link) outlines four key, broad goals that the National Science and Technology Council hopes to achieve within five years: speedy and successful research for future microelectronic technologies, transforming research into manufacturable products, growing and educating the semiconductor workforce, and building ties among different industry players both private and public.

The strategy paper, titled the National Strategy on Microelectronics Research, was written by the Subcommittee on Microelectronics Leadership from the National Science and Technology Council (NSTC), an organization that’s part of the White House. The NSTC helps facilitate the science-related goals of the federal government and the President. Since the CHIPS Act and national competitiveness in the semiconductor industry have been a key priority of the Biden administration, it’s no surprise that the NSTC published a paper on what goals it would like to meet.

A five-year-long strategy might evoke the five-year plans of China and the late Soviet Union. However, unlike those economy-focused plans, the NSTC’s paper doesn’t provide hard numbers it needs the industry to hit, and focuses on a wider variety of topics rather than just the economy. The NSTC describes its paper as “the framework for federal departments and agencies, academia, industry, nonprofits, and international allies and partners” that will help “shape the semiconductor field,” presumably to the benefit of the U.S. and friendly countries.

Four primary goals in five years

There are four primary goals that the U.S. government wants to achieve within the next five years, which are to “Enable and Accelerate Research Advances for Future Generations of Microelectronics”; “Support, Build, and Bridge Microelectronics Infrastructure from Research to Manufacturing”; “Grow and Sustain the Technical Workforce for the Microelectronics R&D to Manufacturing Ecosystem”; and “Create a Vibrant Microelectronics Innovation Ecosystem to Accelerate the Transition of R&D to U.S. Industry.”

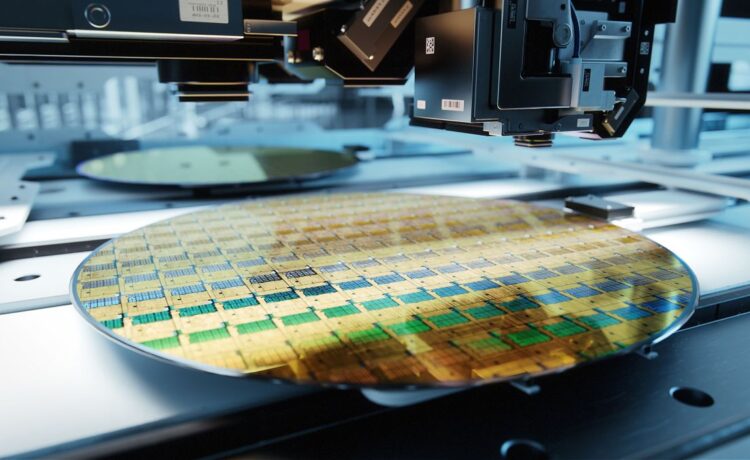

The paper is quite long and complicated but to put it concisely, it says how the CHIPS Act’s funds should be used to improve research and development (R&D), manufacturing, and education. The first goal is focused on R&D for semiconductor materials, tools, packaging, and turning “innovations into production-worthy fabrication processes.” As a counterpart to goal one, goal two seeks to address the “lab-to-fab gap,” as research on its own isn’t very useful. In particular, the NSTC prioritizes small businesses and academia gaining access to resources necessary for fabbing and testing chips.

Education and the semiconductor industry workforce is the concern of the third goal. One part of this is getting educators and students to know about all of the different disciplines that are relevant to the field, even down to the K-12 level. The NSTC also recommends enhancing the curricula of undergraduate and graduate college students, saying “coursework is not enough.”

The paper also recommends engaging with the public at large to raise awareness and curiosity in silicon, and suggests creating museum exhibits and using competitions to get the public interested. The obvious model for these efforts would be NASA, as many Americans learn from an early age about the planets, astronauts, and other space-related topics.

The fourth and final goal focuses on the semiconductor ecosystem and promoting collaboration across its various groups. The NSTC envisions deeper collaboration between entities of all sorts in the public and private sectors, including government agencies, academic institutions, and companies. The paper also puts a particular focus on assisting start-ups, as they require lots of money to get going but may not turn a profit for some time.

It’s clear that the industry is currently very far from reaching the NSTC’s goals outlined in the paper. Right now, most of the focus of the CHIPS Act is funding large corporations like Intel and TSMC so that their American fabs can be completed in a timely manner. Presumably, that’s why the paper assumes five years will be necessary to meet all of these goals, which may be even harder and more important to meet than building fabs.