Crop farmer Kevin Larson knows the ag market in southwestern Wisconsin. On top of growing corn and soybeans, he helps lead the Vernon County Farm Bureau and sells seed to local farms.

Larson said it’s common for producers to start buying seed and supplies in December. But this winter, he and other sales reps have seen a slight decline in prepaid sales with people instead choosing to defer payment until after harvest.

That could be because many producers are holding on to last year’s crops after prices started to decline in the fall.

“People are hoping grain prices will at least jump up a little bit so they can sell their commodities (from last year) and then they’ll buy crop inputs for this year,” Larson said. “But the prices keep declining and people are not selling anything, so cash flow is very tight.”

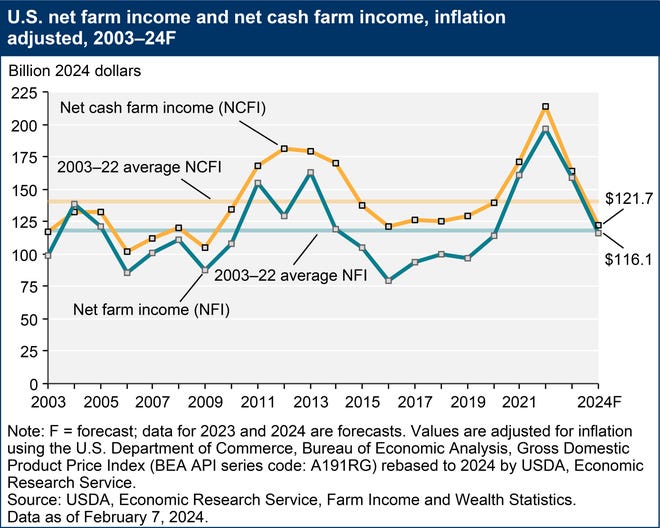

The market outlook isn’t much better for 2024. The latest forecast from the U.S. Department of Agriculture shows net farm income is projected to be 25 percent lower this year than in 2023.

“For 2024, the opportunity for a farm to be profitable is very challenged,” said Aaron Tigert, regional vice president of ag lending and insurance for Compeer Financial. “It’s not unlike other years that most farmers have experienced in the past. It’s just unlike the recent few years.”

Tigert pointed out that 2022 was a record year for farm profitability, with net farm income reaching the highest amount on record at $185.5 billion nationally. That measure declined by 16 percent in 2023, and the projected 25 percent decline for 2024 brings net farm income only slightly below the 20-year average level.

Income decline driven by lower commodity prices, higher labor costs

Lower price forecasts for crops, milk and most livestock means farmers are projected to bring in a smaller income from selling their commodities, according to the USDA’s report. Farmers are also projected to pay 7 percent more in labor costs this year than in 2023. That’s on top of a 5 percent increase in labor expenses last year.

Paul Mitchell, director of the Renk Agribusiness Institute at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, said tight margins are the norm in agriculture.

“You’ve got to keep your costs under control, and hope for good yields and that the market prices for your crops or your livestock are still good,” he said.

He said lower corn and soybean prices will help bring down feed costs for dairy farmers, who saw a significant drop in milk prices last year. The USDA report shows fuel costs are also projected to decline — a savings that will help crop farmers cut back on expenses.

Tigert said farmers will also be looking at land rents, machinery costs and what fertilizers or pesticides they’re using as other ways to save money. He said some farmers have increased their crop or livestock insurance coverage as a way to protect their tight margins.

Many farms ready to weather financial storm, but lack of precipitation still looms

Larson said he’s already planning to cut the amount of fertilizer he’s using by 10 to 15 percent, in part because last year’s drought-affected crops left behind more nutrients in the soil than usual. He also invested in building up his soil fertility during the profitable years of 2021 and 2022, leaving him in a better position as crop prices have declined.

Larson said he invested in new machinery during the same time and saw many of his neighbors pay down their debts.

Mitchell said many farmers made similar financial decisions two years ago, leaving the agricultural sector in sound fiscal shape overall despite the downturn in prices.

“We have a lot of solid balance sheets on average out there,” he said. “The smart farmers locked in these low interest rates back a few years ago, knowing the interest rates were coming up … It’s really the ones that stretched themselves, maybe bought some land at higher interest rates, that are really going to be facing some tough fiscal winds blowing with these tighter margins.”

But for many farmers, Larson said fears about the lack of precipitation this winter far outweigh their concerns over commodity prices.

His farm in Vernon County was one of many who experienced extreme drought conditions across the state in 2023. The southwestern region as well as part of northern Wisconsin are still under severe drought, according to the latest report from the U.S. Drought Monitor.

“(We’ve seen) above normal temperatures, below normal precipitation and we’re going in with a lack of subsoil moisture already from last year,” he said. “If it doesn’t rain and we get a back-to-back drought, it could definitely be a huge deal.”

This article is republished with permission from Wisconsin Public Radio