Retirement planning has undergone a seismic shift over the past few years because of a single factor: higher interest rates. I’ve been taking stock of the implications of higher yields for retirement planning and portfolios, including safe withdrawal rates and asset allocation; Social Security claiming, annuities, and long-term-care insurance; and mortgage paydown.

A related question is how higher yields affect how retirees should approach extracting cash flows from a balanced portfolio. Now that yields are higher, how much of a retiree’s cash flow needs—say, with a 4% spending rate—could be satisfied by spending income and dividend distributions? And what are the pros and cons of spending that income versus reinvesting those distributions and using rebalancing to help supply cash flow needs?

What Do Retirement Portfolios Yield Today?

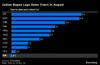

Let’s start by taking a look at what various retirement portfolios might yield today.

A Basic 60/40: A minimalist portfolio composed of 60% in an S&P 500 index exchange-traded fund and 40% in a total bond market ETF would currently pay out about 2.6%, based on the SEC yield of each holding. That’s better than the yield of the same portfolio over the past year—2.1%, based on trailing 12-month yields—but shy of the 4% withdrawal rate that we concluded was a safe starting withdrawal percentage in our recent research. In other words, a retiree with such a portfolio would either need to be able to subsist on a fairly low stream of income or, more likely, would need to use rebalancing to supply additional cash flow needs.

The Bucket Portfolios: Organically generated cash flows look somewhat more encouraging for Bucket investors wishing to subsist off of current income. For starters, the Bucket portfolios all include cash, which is currently yielding more than bonds. (How long that pattern will persist is anyone’s guess.) In addition, the Bucket portfolios include non-US stocks, whereas the aforementioned 60/40 portfolio holds only US equities; non-US stocks generally have higher dividends than US. The inclusion of those assets boosts yield relative to a basic 60/40 mix. For example, the yields on my minimalist ETF portfolios for tax-sheltered accounts currently range from 3.1% to 3.6%. My ETF Bucket portfolios for tax-sheltered accounts have yields in the same ballpark—3.1% to 3.7%. The Conservative portfolios have the highest yields (3.6%-3.7%) because they have more cash and bonds and therefore benefit most from today’s higher interest rates. Meanwhile, equity dividend yields have actually declined a bit over the past year, which explains why the Aggressive portfolios are at the low end of those ranges, just over 3%. The Moderate portfolios’ yields fall between. In other words, the more equity-heavy the portfolio, the less likely it is to deliver a subsistence-level yield. Note that the aforementioned yields don’t factor in taxes, so if a retiree holds the investments in the confines of a taxable account, taxes will haircut the yield by the investor’s tax rate.

But Should You Spend That Yield or Reinvest It?

Given that diversified portfolios’ income distributions alone come pretty close to many retirees’ desired spending rates, the question is: Should retirees go ahead and spend those amounts to meet their living expenses? Or are they better off reinvesting those yields back into their portfolios and relying exclusively on selling appreciated assets via rebalancing to meet cash flow needs? Or perhaps they should use a hybrid approach, spending their yields but selling appreciated securities to meet additional cash flow needs?

Each of these approaches has its own pros and cons.

Strategy 1: Spend the Income

Spending a portfolio’s income distributions is one of the most intuitive ways to generate retirement income, which helps explain why so many retirees gravitate to it. Moreover, bequest-minded retirees like this approach because spending income rather than touching principal helps ensure that there will be leftovers for heirs.

There are a few drawbacks to using yield to supply living expenses, however. The big one is that subsisting on income means that a retiree gets buffeted around by the prevailing yield environment. While organically generated yields on diversified portfolios are nearly 4% today, just two short years ago they were roughly half that amount, meaning that a retiree tethered to his or her portfolio’s income distributions would have had to choose between underspending or juicing yields with higher-risk securities. And while equity dividends are often more stable than income from bonds and cash, they’re not set in stone. In a significant economic downturn, dividend-paying companies may cut their dividends and in turn force down the spending of income-dependent retirees; many banks did just that in the global financial crisis of 2007-09.

Additionally, our research points to retirees’ being able to spend more from their portfolios as they age, whereas an income-centric approach makes no such adjustments. (Payouts will be higher for the income-centric retiree if the total portfolio gains in value over his or her lifecycle, but that appreciation isn’t a given.) Finally, yields on dividend-paying stocks and lower-quality bonds frequently spike in market downturns, fueled by uncertainty or worries over impending economic weakness. During such periods, reinvesting income distributions from beaten-down securities rather than spending them will improve the portfolio’s long-term appreciation potential.

Strategy 2: Reinvest the Income; Use Rebalancing to Generate Cash Flows

Under this strategy, a retiree reinvests all income, dividends, and capital gains back into the portfolio. The retiree then periodically scales back on those holdings that have performed the best, whether stock or bonds, to bring the total portfolio’s asset-class exposures back in line with targets and to supply ongoing cash flows.

In contrast with the income-centric approach outlined above, a reinvest/rebalance strategy effectively forces the retiree to sell appreciated assets on a regular basis, while leaving underperforming assets in place or even adding to them. In so doing, it simultaneously addresses cash flow needs while also maintaining the retiree’s desired portfolio mix. The retiree also has control over the withdrawal amount, so he or she can increase withdrawals with age or ratchet down withdrawals to maintain a more fully invested stance in weak market environments.

The major drawback with this approach is that there will be years when nothing has appreciated, and in turn, there are no obvious securities to sell to meet living expenses. The year 2022 was a perfect example: The Morningstar US Market Index dropped 21%, and high-quality bonds lost 13%, so a retiree with a fully invested portfolio would be forced to sell depreciated securities into weakness in order to meet cash flow needs. A similar phenomenon occurred in 2018, when both stocks and bonds posted losses at the same time, albeit more modest ones than 2022. A Bucket approach, whereby the retiree sets aside cash reserves to help meet withdrawals during such a period, helps address that shortcoming, albeit with the long-term return drag that typically accompanies cash versus a fully invested portfolio.

Strategy 3: Spend the Income and Use Rebalancing Proceeds to Supply the Difference

Under this strategy, a retiree spends income distributions from cash holdings, bonds, and dividend-paying stocks. If those distributions are insufficient to meet spending needs, the retiree can look to rebalancing proceeds to supply additional living expenses. And if both of those sources are insufficient to supply cash flow needs, or if stocks and/or bonds have dropped in value and the retiree would rather reinvest income distributions, spending from cash can come into play.

The big advantage of this approach is that it supplies a baseline of income for living expenses, even when stocks and/or bonds are down. In so doing, it may provide peace of mind for some retirees. Retirees might also take comfort in the inherent optionality and flexibility of this approach: Depending on the market environment, cash flows can come from income, rebalancing, and/or cash in a pinch.

One minor quibble is that such a strategy might not provide the same tight control over the portfolio’s asset allocation that a strict “reinvest and rebalance” approach might.

Flexibility Is Ideal

While higher yields now make subsisting on income a realistic possibility for retirees with balanced portfolios, my bias is with Strategies 2 or 3 above. (With Strategy 2, I like the idea of bolting on a cash bucket rather than going fully invested.) Both approaches give the retiree more discretion over the size and source of cash flows on an ongoing basis, providing more flexibility to adapt to evolving markets as well as their own changing preferences on spending. Moreover, with the Federal Reserve widely expected to cut interest rates later this year, income-centric retirees may find themselves right back where they were in early 2022, with a choice between lowering portfolio cash flows or taking on more risk to get yield where they need it to be. Neither is apt to be especially appealing.