The fevered debate about the shrivelling of the London stock market has identified numerous possible causes. Blame for the sharp fall in the number of quoted companies is laid on everything from the UK’s excessively onerous corporate governance rules to its relentlessly negative financial media.

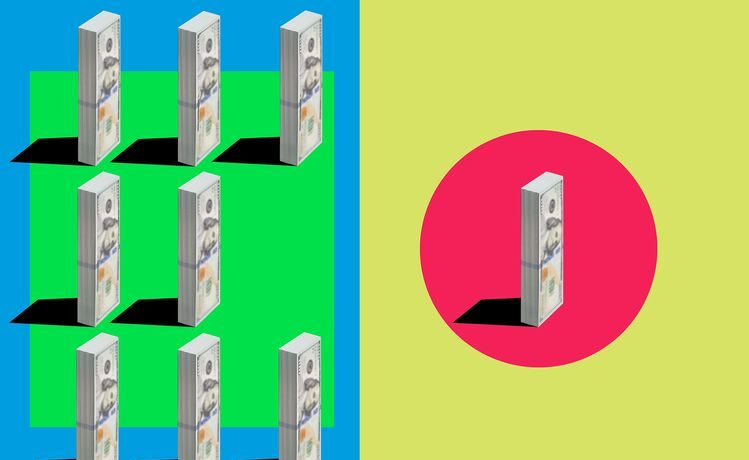

Yet there are two things that really matter: valuations and liquidity. Most companies that turn their backs on a stock market listing in London say it is because they will get a better price and higher trading volumes in their shares elsewhere — usually New York.

The London Stock Exchange and its supporters have tried to counter these claims. LSE Group boss David Schwimmer insists it is a “myth” UK-listed companies suffer a valuation discount to their US‑listed counterparts. But few seem convinced.

Sceptics point to the fact that the earnings multiple for the US market is more than 40% higher than the UK’s. Yet, as I pointed out recently, when UBS made a strict, like-for-like comparison of individual stocks, it found there was either no discount or even a small premium for the UK firms, in about 40% of cases.

READ Banks and fund execs split on London’s chances of staying on top

The headline liquidity numbers look even worse for London. Trading volumes on the LSE have fallen sharply in recent years, while the figures generally quoted for the US exchanges look much healthier.

Yet all these statistics need to be treated with care. If you look on a Bloomberg or Refinitiv terminal, the figures for equity volumes in London relate solely to the trades carried out on the LSE. But the figures quoted for the US and EU countries include trades carried out on platforms other than the main exchanges.

The LSE tried to point this out in a blog post it published last summer. The LSE’s head of equities trading product, Tom Stenhouse, compared total volumes across all platforms in the UK and the US relative to the free float of companies’ shares. This gives a dramatically different picture: the FTSE 100 and FTSE All Share are slightly ahead of the S&P 500 and Nasdaq 100, with the FTSE 250 slightly below.

But Stenhouse added a caveat that fatally undermined his argument: some of the volume that takes place off the main exchanges includes “non‑addressable liquidity” — trading that is not open to all market participants and “does not contribute to price discovery”.

The market structures in London and New York are very different so you would not expect the proportion of non-addressable liquidity to be the same. Yet this is not captured in the total volume figures, which are therefore likely to be a poor guide to effective liquidity.

Whatever the figures show, many companies believe liquidity in New York is much better.

Kazakhstan-based fintech firm Kaspi listed in London in 2020, but recently raised $1bn through an issue of shares on Nasdaq. Kaspi said the New York exchange offered higher valuations and better liquidity than London’s. Feedback from investors was that liquidity in London was a real issue — the low trading volumes meant it took them too long to build up a significant holding; some had even been forced to sell because the tripling of the firm’s share price since it listed meant they had run up against their fund rules on illiquid holdings.

Yet one veteran equities banker doubts liquidity is a serious problem for most London-listed companies. Although he admits the data for the different markets are hard to find and tough to interpret, he found when he crunched the numbers that the LSE has a reasonable case.

READ ‘This lazy trope that New York is the right market for everybody is wrong’

So why has the LSE not done a better job of countering the liquidity claims?

Perhaps because it can’t quite decide what line it should take. Should it run with: “Liquidity is terrible — we need help”? Or should it be saying: “Look at the figures: liquidity isn’t a problem”?

If the LSE decides it needs to ask for help, the obvious way for the government to assist it is to cut the 0.5% stamp duty on share purchases. This tax makes the UK less attractive as a venue, particularly for high-frequency traders, which are important providers of liquidity these days.

However, it also raises about £4bn a year. The LSE would therefore need a very compelling case that cutting the levy would be a good use of public money.

If, on the other hand, the LSE wants to argue that liquidity isn’t a problem, it really must do a better job with the data. The introduction of a consolidated tape that records all trades would help but it can’t wait for that. It should be pressing the Financial Conduct Authority to require better reporting from all trading venues now.

In terms of addressable liquidity, the LSE needs to produce a much more convincing comparison between London and New York as soon as possible. If this is so important, it needs to raise its game.

To contact the author of this story with feedback or news, email David Wighton