Even if the FTSE 100 index was testing the 8,000 level again on Friday it was still yet another terrible week for the London stock market.

E-therapeutics became the latest company to delist its shares, with its chief executive, Ali Mortazavi, complaining that the market was completely “broken”.

In the background, Shell has started warning ominously that it might consider shifting its listing to New York, given that American oil companies trade on far higher ratings, and there was even speculation that BP was now so cheap compared to global rivals that it might get taken out by a Middle Eastern buyer. If either of the two oil giants were lost, then the London market might as well pack up completely. The game would be over.

The London Stock Exchange may be in very bad shape. But we should not kid ourselves that it is alone. In his annual letter to shareholders this week, Jamie Dimon, probably the most powerful man in global finance, highlighted that Wall Street was starting to go the same way. At its peak in 1996, there were more than 7,000 publicly traded companies for investors to choose from, but now that has fallen to only 4,000.

“The total should have grown dramatically, not shrunk,” argued Dimon. That is surely true. After all, the American economy is a lot larger than it was 25 years ago. Indeed, strip out the Magnificent Seven, as the major tech companies are known, and the US market has performed almost as badly as the British one.

That is happening despite an economy that is still growing, where there is a huge tech industry that leads on innovation, where returns have outstripped most of the rest of the world, and where there is a healthy base of private investors with money to support the market. Wall Street has none of the challenges that the City faces, yet its leading figures are still worried about the rate at which it is shrinking.

In fact, there is a bigger trend at work: global equities are moving east. In India, flotations are booming. A total of 184 companies listed their shares in the country in 2023, and there were another 21 in January alone, with further 66 already in the pipeline for the rest of this year. Sure, not all of them are of the highest quality, but then they are not in the West either.

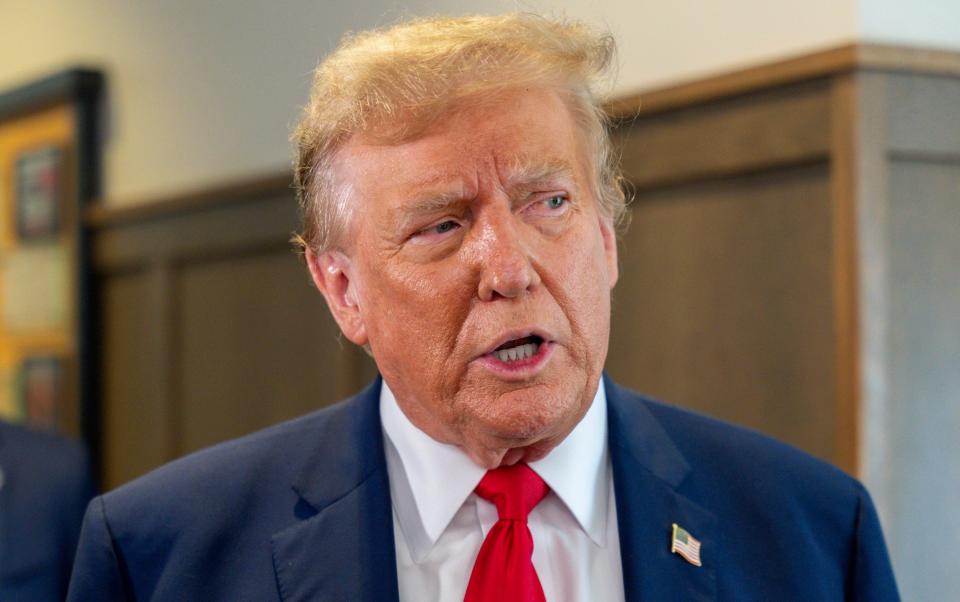

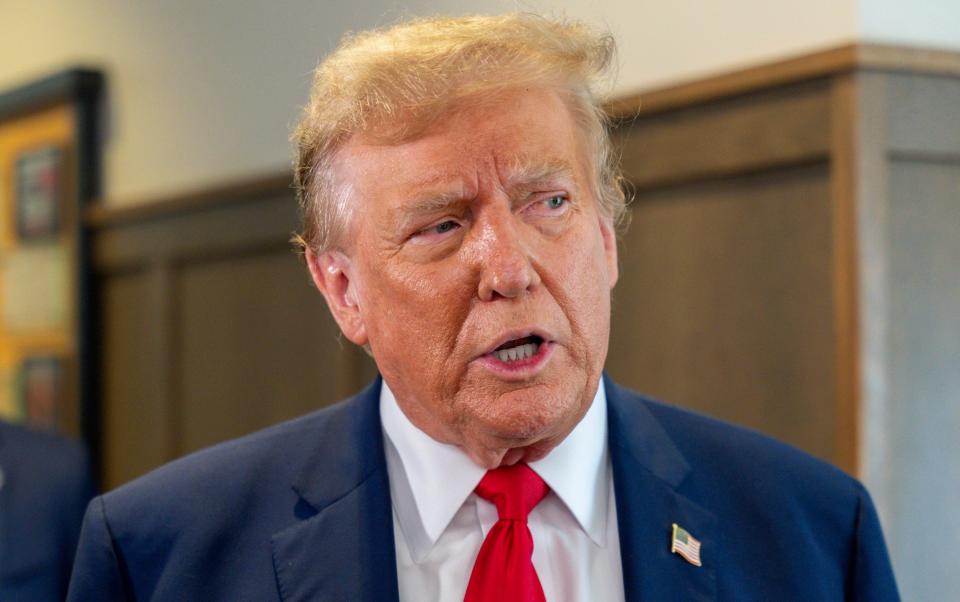

After all, London listed flops such as Deliveroo, while New York’s market recently welcomed Donald Trump’s Truth Social, hardly the world’s safest investment. India’s listing boom will be a mixed bag, but there will be some gems in there, and they will emerge over time.

Likewise, the Shanghai market may well have been weak over the last few years as the Chinese economy slows down, but has still doubled the number of companies listed over the last decade, and it may well improve this year as big names such as fashion retailer Shein, and the electric vehicle manufacturer Zeekr, sell shares to the investing public.

Overall, the Asia-Pacific region hosted more than 700 flotations in 2023, raising more than $73bn, more than half the global total. There is no sign of that trend slowing down. Indeed, with new capital markets such as Indonesia – with 79 flotations in 2023 and another 65 scheduled for this year – starting to thrive it will only accelerate.

In reality, the difficulties faced by all the major Western stock markets make one thing clear: this is not just a British phenomenon. Leaving the EU probably didn’t help, neither does stamp duty on share trading, or our hopelessly low levels of saving and investment. And yet in reality, those are all relatively minor factors. Stock markets are in rapid decline right across the developed world. It is nothing to be proud of, but we are simply ahead of the curve.

Here in the UK, or in Paris or Frankfurt, we can make some minor tweaks and reforms. We can slightly ease up on listing rules, and relax some of the idiotic governance codes, as well as encouraging the pension funds to invest more of their money at home. But nothing can stop the great shift eastwards.

Much as you might expect, equity trading is just going where the money is. There are inevitable bumps along the way, but the Asian economies are growing a lot faster than the US, and dramatically faster than anywhere in Europe.

In the developed world, the market is dominated by old, established giants that are often a century or more old. They consolidate constantly to try and preserve their profits but they rarely expand, and each time they merge the number of listed companies declines.

In India, China and even more in markets such as Indonesia, there are new companies emerging all the time. They need capital to help them expand, and their founders need a way of cashing in on their fortunes.

That trend is irreversible, and no matter what we do to try to rescue London nothing is likely to stop it steadily becoming more marginal to the global equity market.