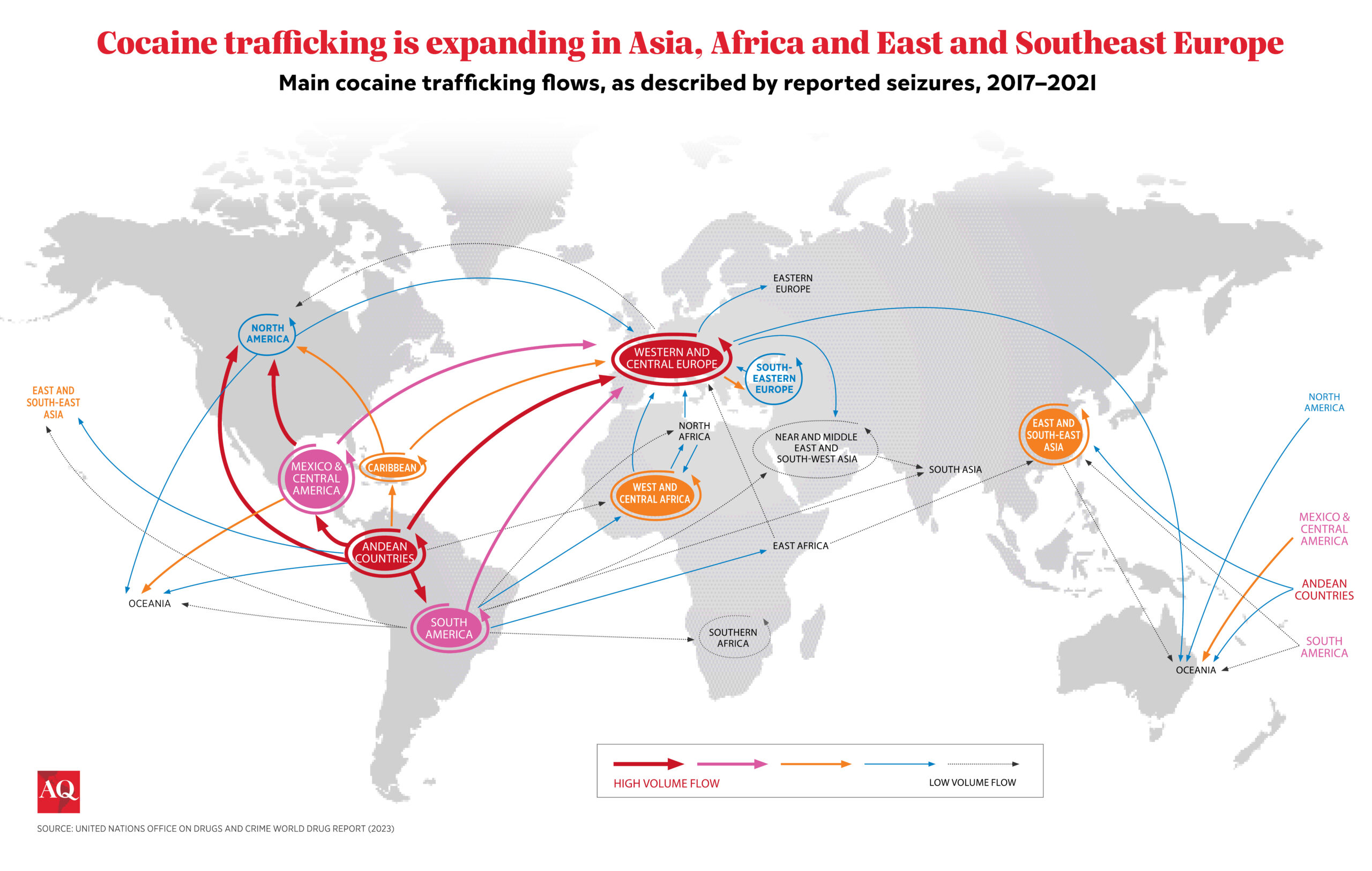

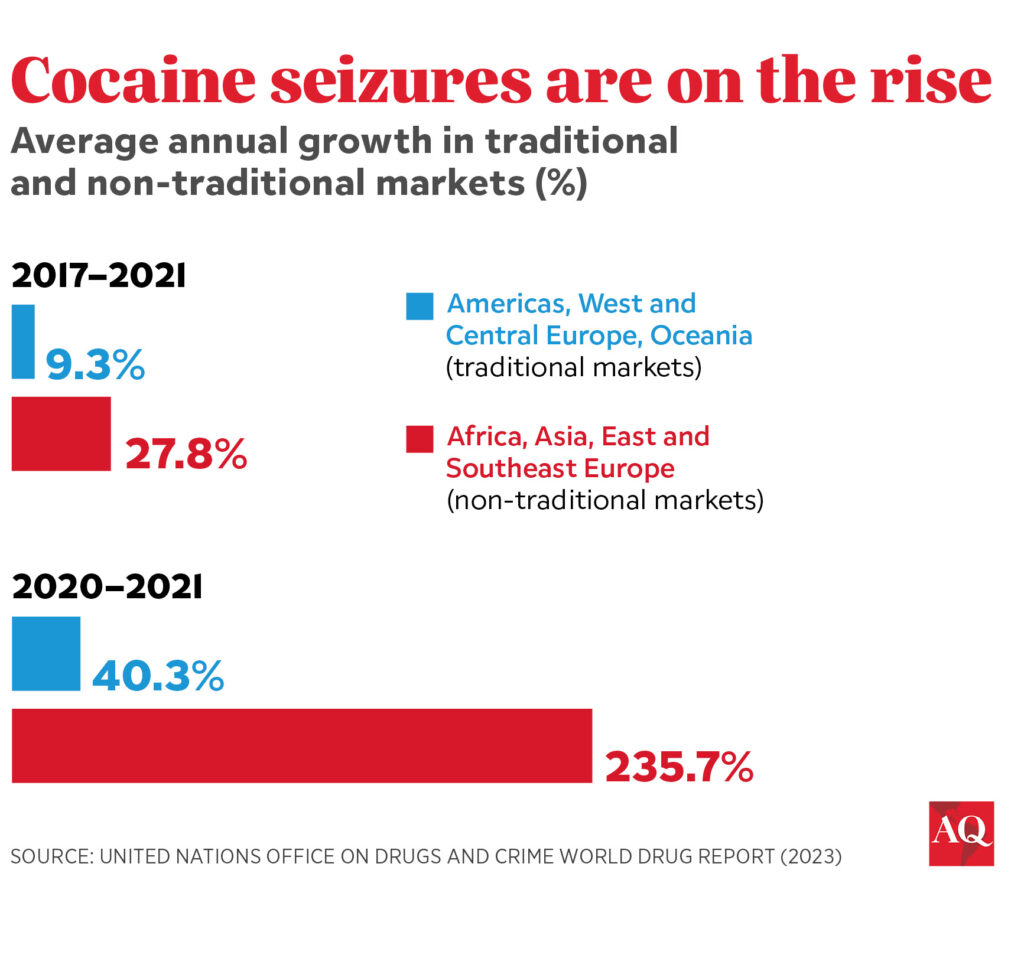

For a rising number of Latin American drug cartels, being global is nowadays a “do-or-die” proposition. Hemmed in by the oversaturation of the U.S. market and the increasing preference of U.S. consumers for synthetic drugs, such as fentanyl, these organizations have eagerly expanded their cocaine smuggling to Europe in recent years. Now, they are looking for new markets, and Asia is the name of the game.

After a remarkable increase in drug production over the last decade to a record level of almost 2,000 tons of pure cocaine per year, drug lords are betting on China, India and South Korea’s markets. The output increase is taking place thanks to recent investments in technology to raise coca bushes’ productivity and the expansion of the cultivation area to non-traditional countries in Latin America, the sole producer of all the cocaine sold worldwide.

The push for higher production and market expansion has brought an increase in drug-trafficking-related violence to the region. In January, gangs kidnapped correctional officers and invaded a TV station in Guayaquil, Ecuador, representing an unprecedented wave of drug-related violence in a nation that not long ago was a peaceful Andean destination.

It’s not a mere coincidence that the leading Mexican gangs, the Sinaloa Cartel and Cartel Jalisco Nueva Generación, or CJNG, have Ecuador as their latest and most prominent battlefield, as both are engaged in fierce competition to control key territories and markets in the Western Hemisphere and beyond. Both organizations have set their sights on Asia since getting local prominence, but the Sinaloa Cartel has an early advantage in this expansion. According to some scholars, Joaquín “El Chapo” Guzmán, the incarcerated drug lord enduring a life sentence in Florence, Colorado, created import and export networks in Asia in the early 2000s, liaising its thriving group with Chinese gangs, including 14K and Sun Yee On, in Hong Kong.

Latin American political leaders gathered in Cali, Colombia, last September to address new policies on drug trafficking, and the presidents of Colombia and Mexico urged the creation of a new international anti-drug policy. Colombia’s Gustavo Petro went further and said that the militarized approach to combat the illicit trade, known as the war on drugs, has failed. It’s estimated that close to 6% of the global population uses illegal drugs.

As the region’s leadership struggles to find the best policy to fight drug trafficking, increasing commercial ties are setting the stage for a new reality. Trade relations between Latin American and Asian countries have made transportation faster, cheaper and permeable to illicit activity. Countries like Ecuador, Peru, Chile, Nicaragua and Costa Rica have signed free trade agreements with China, adding to the increasing trade between China and Colombia, Brazil and Argentina. (Colombia, Peru and Bolivia are the largest cocaine-producing countries in the world.)

The relevance of China and India

South America’s cocaine production is flooding the region’s countries, and the ports of San Antonio (Chile), Buenos Aires (Argentina) and Montevideo (Uruguay) have gained importance as the cocaine departs from there to Europe, Oceania and Asian markets. Air routes are also crucial since they can quickly respond to a concrete demand. In that case, mules (people carrying cocaine in their stomachs) are being used to traffic cocaine from South America (from Brazil, in many cases) to Europe and East Africa and from there to Asia.

China and India are critical to understanding how the cocaine market is being developed in Asia. Although very little data is available regarding China’s seizures of cocaine, the country has become a transshipment point for cocaine coming from Latin America, according to the Global Organized Crime Index. China is the world’s biggest hub for container movement, facilitating easy access and cheap transportation for licit and illicit goods. Rising drug seizures in Hong Kong, Macau and mainland China seem to prove this trend.

In the case of India, even though the domestic market remains tiny, cocaine smuggling has risen in recent years, driven by tourism, as criminal organizations use the internet for sales, payments and distribution. According to official data, cocaine seizures have increased dramatically, and even when numbers are not high enough, concerns have been raised, particularly around container movement.

South Korea has become a significant hub of cocaine going to China, Oceania and other parts of Asia. The port of Busan plays an essential role in the arrival of cocaine from Latin America, given its crucial position in Northeast Asia (ranking sixth in global importance), considering the number of containers moved. Japan, on the other hand, remains largely outside the worldwide cocaine market—despite reports in some quarters to the contrary.

How the landscape is changing

While the U.S. and Brazil are still the most important cocaine consumers worldwide, the cocaine market seems to be displacing geographically from the Americas to Europe. According to the European Drug Report 2023, close to 2.3 million 15- to 34-year-olds (2.3% of this age group) used cocaine. The report highlights that after cannabis, cocaine is the second most used illicit drug in Europe, although prevalence levels and patterns of use differ considerably between countries. Even though the current cocaine market has become Eurocentric, that trend may change in the years to come, as cocaine prices in Asia have recently skyrocketed.

New markets for drug consumption are constantly emerging thanks to criminal organizations’ bid to stimulate demand for the extra cocaine produced every year (and thereby increase their profits). Now, Asian markets are assuming a more significant role. Many of these countries are already involved in global drug markets, but in a different manner: Asia, and particularly China and India, provides precursor chemicals used to produce drugs in the Americas, as well as fentanyl itself.

The new reality raises the question of whether governments will fight the development of criminal organizations separately or cooperate against this rising transnational threat. Latin American countries can cooperate with Asian countries, sharing the know-how they have gained during the last decade and the cooperation mechanisms they have developed, for example, with Europe. The critical question is whether the political will to do so exists.

—

This article shares some of the highlights of a book chapter in Cocaine: Criminals, Routes, and Markets, by S. Cutrona & J. Rosen. University of New Mexico Press (forthcoming).

Sampó is a researcher from the National Scientific and Technical Research Council (Conicet), Argentina. She is also one of the coordinators of the Center for Studies on Transnational Organized Crime (CeCOT), International Relations Institute (IRI), University of La Plata (UNLP), Argentina.

Troncoso is the co-coordinator of the Center for Studies on Transnational Organized Crime (CeCOT), International Relations Institute (IRI), University of La Plata (UNLP), Argentina.

Tags: Asia, cocaine trafficking, Security

Any opinions expressed in this piece do not necessarily reflect those of Americas Quarterly or its publishers.