At the end of 2023, the San Francisco district attorney’s office lost out on $3 million in potential restorative justice funds from the philanthropic foundation Crankstart, according to documents obtained in a public records request and shared with Mission Local.

The foundation, in a three-year grant that began under then-District Attorney Chesa Boudin, pledged up to $6 million to fund a restorative justice program in San Francisco. Known as the “Healing Justice Initiative,” it diverted people from prosecution by creating alternative forms of accountability.

Crankstart is the personal foundation of billionaire Michael Moritz and his wife, the novelist and sculptor Harriet Heyman. Moritz is a venture capitalist who is deeply involved in San Francisco politics, giving or pledging some $17 million to the public pressure group TogetherSF and spending heavily to get law and order mayoral candidate Mark Farrell elected.

The DA’s office accepts millions in outside grants from foundations and the state to fund various programs, and Crankstart’s $6 million was its largest grant ever.

The program run by the DA’s office and funded by Crankstart was started as a pilot project under Boudin but never fully got off the ground. If victims and offenders both agreed, offenders would apologize to their victims and take a series of remunerative steps, like paying restitution for a robbery or attending programs, usually overseen by a nonprofit. The program focused on adults and transitional-aged-youth — those between 18 and 24.

Under Boudin, the DA’s office hired staff and partnered with nonprofits, staffing up to make referrals. It received $1 million from Crankstart in 2020 to start the program. The grant had a three-year term, from Jan. 1, 2021, to Dec. 31, 2023.

But immediately upon assuming office in mid-2022, District Attorney Brooke Jenkins halted all restorative justice referrals for adults. She said at the time the move was temporary, but her office never resumed adult referrals. That, several people close to the program said, was surprising, as restorative justice programs have been shown to reduce recidivism, and even tough-on-crime proponents see their value.

“It really slowed our work. There were so many delays, so many points of indecisiveness — it was really confusing,” said Sandra Rodriguez, at the time a restorative justice program specialist at Impact Justice, one of the nonprofits tapped to work with the DA’s office on the grant. “Really, when Brooke Jenkins took over, it completely halted.”

The lack of attention on restorative justice convinced Crankstart to cease funding, according to several people close to the program. The DA’s office on Dec. 11, 2023, specifically requested an extension, citing Jenkins’ “support of restorative justice practices.”

But Crankstart subsequently informed the DA’s office that it would not grant the extension. The DA’s office, which could have received up to $6 million for the program, effectively left half on the table.

Crankstart declined to elaborate on why it stopped funding.

“We continue to believe in the power of restorative justice, and in the need to respond to what communities are asking for when it comes to criminal justice reform,” said Jesse Hahnel, a program director for criminal justice reform at the Crankstart Foundation.

The DA’s office, in a statement, pushed back on the assertion that movement was slow and laid blame at the feet of Boudin’s administration. Boudin’s office “never operationalized” the program and was slow to spend funds, Jenkins’ office wrote; former Boudin-era staffers and nonprofit partners said they were moving quickly when Boudin was recalled in 2022.

“In recalling Chesa Boudin the voters gave me a clear mandate to put an end to his reckless social experiments that compromised public safety in service to a failed ideology,” the statement from Jenkins continued, calling it “absurd to question my administration’s commitment to restorative justice.”

The city still has myriad other diversion programs to avoid convictions and prison time, like a drug court and veterans court, both of which connect offenders to treatment or services. Restorative justice programs, however, are different: They also allow offenders to avoid charges, but only if they acknowledge their crimes to victims and remedy them. The city’s only current such program is called Make It Right and was started in 2013; it applies to offenders aged 13 to 17.

But the Crankstart-funded program was the first restorative justice program to focus on adult offenders, who could have avoided charges as long as they were completing steps in an accountability plan. Importantly, victims had to agree to the program. Under Boudin, eligible crimes included felonies and high-level misdemeanors, but excluded violent crimes like homicide, sexual assault, and rape.

Angela Chan, the assistant chief attorney at the San Francisco public defender’s office, said in a statement that Jenkins’ rationale for the program ending was wrong. The DA’s office “essentially killed” the restorative justice program “by seeking to narrow its scope to apply to only low-level charges” she said, calling it a “rash decision that was harmful to victims, our clients, and the many community-based organizations who had hired staff and devoted time” to the program.

Restorative justice programs have been shown to reduce rearrest. A January 2024 study found that youth in San Francisco’s Make It Right program, run by the city and partly funded by the Zellerbach Family Foundation, were 44 percent less likely to be rearrested compared to those undergoing traditional felony prosecution. San Francisco’s Neighborhood Courts program, another such program, saw 90 percent of its 24,000 cases between 2011 and 2021 successfully completed without charges from the DA, according to a 2022 DA’s office memo.

A 2023 study, citing a slew of other studies, noted double-digit reductions in recidivism across more than 20 such programs nationwide. The United Nations found successful restorative justice programs in countries from Laos to Mexico.

“We hope that the DA’s office will continue to prioritize diverting people from the criminal justice system when that’s in the interest of justice and in the interest of community safety,” said Hahnel from Crankstart.

The DA’s office has lost at least two criminal justice reform grants under Jenkins. In August, the MacArthur Foundation informed the office it would withhold $625,000 of a grant that was meant to reduce the city’s jail population. The foundation cited a dramatic rise in San Francisco inmates and questioned the office’s commitment to reform; the DA’s office wrote it would “not be used as sharecroppers to a Foundation’s vision of criminal justice reform.”

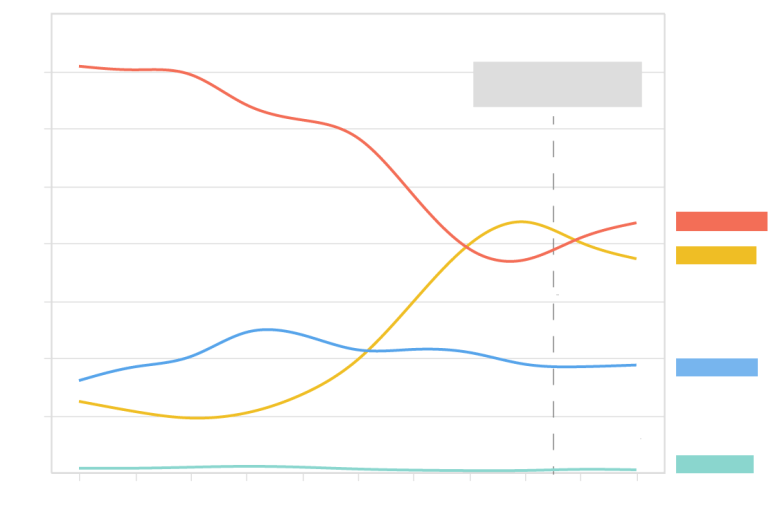

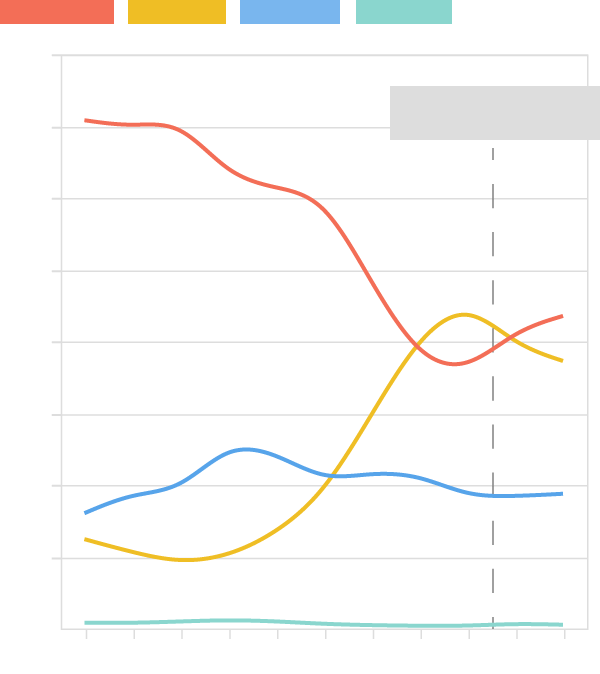

Diversions, by which individuals can have their charges dismissed if they agree to alternative programs, have declined under Jenkins: They went from 45 percent of all cases in 2022, the year Boudin left the office, to 37 percent so far this year, according to the DA’s office. Convictions, meanwhile, have risen from 36 percent of all cases in 2022 to 44 percent. Jenkins reversed a years-long decline in convictions that began in 2016.

After a decade-long fall, convictions are on the rise

Since Brooke Jenkins became district attorney, the rate of convictions has risen, and the rate of diversion programs has fallen. Take a look at the rates of cases resolved by different outcomes:

DA Boudin recalled,

Jenkins appointed

DA Boudin recalled,

Jenkins appointed

Chart by Kelly Waldron. Data from the San Francisco District Attorney’s Office.

Jenkins, who campaigned against her former boss Boudin before being appointed to his post by Mayor London Breed, appears to have reversed a focus on reform in favor of traditional prosecution. All of the police shooting cases in which Boudin had charged an officer were dismissed by Jenkins within a year of her tenure, for example. As a result, dozens of staffers have left the office, saying it no longer focuses on reform.

After the grant was dissolved, nonprofit partners were left scrambling. Rodriguez, who was then at Impact Justice, and Celi Tamayo-Lee from San Francisco Rising, another nonprofit partner, said their organizations had hired staff in anticipation of running the program, only to have those funds disappear.

After nonprofits spoke up about the collapse of the grant, Crankstart stepped in and backfilled funding by directly giving to the nonprofits, both said. “They made all the nonprofits as whole as possible,” added David Mauroff, the CEO of San Francisco Pretrial Diversion Project, another nonprofit partner. “They really stepped up. They didn’t have to do that.”

But the work those nonprofits were planning on adult cases has ended. Even though restorative justice is a “bipartisan issue,” according to Rodriguez, because of its efficacy in reducing rearrest and recidivism, San Francisco’s experiment with expanding it to adults is over. “It felt like Brooke Jenkins’ office single-handedly brought us back a decade.”